No hospitals named in tales of infection

Report on diseases acquired during medical procedures keeps institutions anonymous

By CATHLEEN F. CROWLEY, Staff writer First published: Wednesday, July 9, 2008

ALBANY -- Three years after a law requiring hospitals to report their infection rates to the state passed, the numbers have been released -- sort of.

The hospital-by-hospital rates for 2007 will not be fully disclosed. Instead, New Yorkers can see aggregate rates, an interim step negotiated by the hospital industry when the law was enacted in 2005.

"The promise that was made to (the hospital community) was we will do this right," said Assemblyman Richard Gottfried, chairman of the Assembly Health Committee, "to make sure it's running right before we take it public. That was an important promise and a smart promise."

The hospital-specific numbers will be revealed next year and every year thereafter. Meanwhile, the public can view the 2007 hospital-by-hospital rates on the state Department of Health's Web site, http://www.nyhealth.gov, but the names of the hospitals are masked.

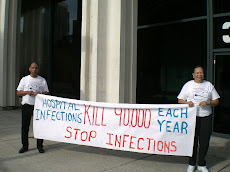

According to the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, there were an estimated 1.7 million health care-associated infections nationally and 99,000 deaths from those infections in 2002. Hospital-acquired infections are considered preventable with good hand-washing, equipment sterilization and proper procedures.

Capital Region hospitals refused a request from the Times Union to voluntarily release their infection rates on Tuesday, saying they will follow the state's timeline for unveiling the information.

"It allows us and all hospitals to take a look at the statewide data and compare it to make sure it's accurate and complete and we are all comparing apples to apples," said Brad Sexauer, Saratoga Hospital's vice president of strategy and marketing development.

Arthur Levin, director of the Center for Medical Consumers and a member of the state's advisory board for the reporting system, defended the anonymity granted to hospitals this year.

Levin said it will assure that the data is accurate, and next year, "hospitals will have no excuses."

According to the aggregate figures released Tuesday, New York's infection rates mirror the nation's. For every 100 people who undergo colon surgery, about six get an infection, according to the report. For people who have a coronary bypass graft, 3.6 out of every 100 get an infection. Fewer than 1 percent develop infections related to central lines, which are tubes that snake through a vein to the heart to deliver medicine and monitor heart function.

Of all reported infections, about 10 percent were caused by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus or MRSA. The rest were caused by organisms that respond more easily to antibiotics.

Betsy McCaughey, the former New York lieutenant governor who has since founded the Committee to Reduce Infection Deaths, said the report has many shortcomings -- most notably the comparison to national rates.

"The only infection rate that is acceptable is zero," McCaughey said.

McCaughey criticized the report for highlighting risk factors for infections, like gender and obesity, without exploring the most important contributors: unclean hospitals and lax procedures.

Wednesday, July 9, 2008

Monday, July 7, 2008

100 Mistakes A Month

Serious patient errors at California hospitals disclosed in state filings

About 100 Californians a month are being harmed in adverse events considered preventable. A lawmaker proposes banning reimbursements to hospitals for some types of injuries.

By Jordan Rau, Los Angeles Times Staff Writer June 30, 2008

SACRAMENTO -- Last October, a technician at the children's hospital at Stanford University improperly connected a ventilator hose, accidentally pumping too little oxygen into a 9-day-old infant's lungs.

A month later, technicians at Dominican Hospital in Santa Cruz unintentionally placed a CT scan of one patient into the electronic file of another, leading physicians to remove the wrong person’s appendix.

Last March, Virginia Fahres, 76, died at Pomona Valley Hospital Medical Center in Pomona after a nurse gave her two drugs, neither of which her doctor had prescribed.

Those incidents were among 1,002 cases of serious medical harm disclosed by California hospitals between July 2007 and May of this year. The disclosures are the first under a state law that requires hospitals to inform health regulators of all substantial injuries to their patients.

Officially called “adverse events,” those accidents are also known as "never events" because they are considered preventable, and many safety experts say they should never happen. California patients are being injured at a rate of about 100 a month, according to data compiled by the state Department of Public Health.

"I think the never events are a wake-up call to everyone about the safety of California hospitals," said Beth Capell, a lobbyist for Health Access California, a consumer group.

Revelations of such errors have led lawmakers and hospital associations in at least seven states to protect patients from having to pay for the cost of care that went awry. In Sacramento, an assemblyman proposed a ban on reimbursing hospitals for the types of injuries tracked by the state. But when lobbyists for doctors and hospitals objected, he scaled it back to cover far fewer errors.

Four million people were admitted to California hospitals last year. State investigators found some errors occurred because hospitals failed to follow safeguards designed specifically to prevent harm.

Last July at UC San Diego Medical Center, a patient died after a nurse incorrectly programmed a medicine pump that then delivered more than twice the appropriate dose of a specialized blood pressure drug. Regulators found that the hospital's administration had been warned earlier by its own safety committee that "errors continue to occur" with that type of pump but had not taken sufficient corrective action, according to a state probe.

UC San Diego officials said they have since held repeat drills with staffers who treat patients with Flolan and examined every step in the process.

Dr. Angela Scioscia, the center's senior medical director, said the public reporting requirement is "a great opportunity to make rapid improvements" because hospitals can learn from one another's problems. "We don't want people to be afraid when they come into hospitals, because they are becoming safer and safer all the time," Scioscia said.

Under the 2006 disclosure law by state Sen. Elaine Alquist (D-Santa Clara), hospitals must inform state regulators of every occurrence of 28 different types of dangerous mistakes. Those include deaths during labor, medication errors, suicide attempts and sexual assaults.

The public health department has until 2015 to begin posting the information on the Internet, although officials said they hope to begin publishing it earlier. The most recent figures available cover the 10 months since July 2007. In that time, 466 patients developed bedsores so severe that the dead skin formed a crater or rotted through to the muscle or bone.

Another 145 patients had foreign objects such as surgical equipment left in their bodies. Thirty-four died while under anesthesia. In 41 surgeries, doctors performed the wrong procedure or operated on the wrong body part or on the wrong patient.

So far, the state Department of Public Health has levied $25,000 fines against 10 hospitals that reported adverse events. Officials said other investigations are still under way.

One hospital, Scripps Memorial in La Jolla, was fined twice for two errors that occurred last November with the same patient. First, as the patient was recovering from surgery, she was given a painkiller that is not supposed to be used after operations. When she went into respiratory arrest, the pharmacist provided a corrective medication at a dose 10 times too weak to be effective.

The patient survived. State investigators discovered that the hospital's pharmacists had not been properly instructed in the use of 10 medications, including the corrective drug, that the hospital stocked for emergencies.

The ventilator error at Stanford's Lucile Packard Children's Hospital occurred because a therapist had assembled the machine by following a diagram that had been drawn backward. Dr. Christy Sandborg, the hospital's chief of staff, said the medical team quickly noticed that the ventilator wasn't working correctly and stopped using it. The child recovered, she said, and the hospital has made changes to prevent future occurrences.

Overcrowded emergency rooms are another factor behind patient injuries. A 2006 study found that California had fewer emergency rooms per resident than any other state.

At Kaiser Foundation Hospital San Jose in March, staffers left a patient waiting in the emergency room for more than an hour after a test showed that his blood sugar was higher than the maximum measurable with a glucometer. The medics determined that he needed immediate care, but all 25 treatment bays were full. He passed out in the waiting room and died from heart failure.

About 100 Californians a month are being harmed in adverse events considered preventable. A lawmaker proposes banning reimbursements to hospitals for some types of injuries.

By Jordan Rau, Los Angeles Times Staff Writer June 30, 2008

SACRAMENTO -- Last October, a technician at the children's hospital at Stanford University improperly connected a ventilator hose, accidentally pumping too little oxygen into a 9-day-old infant's lungs.

A month later, technicians at Dominican Hospital in Santa Cruz unintentionally placed a CT scan of one patient into the electronic file of another, leading physicians to remove the wrong person’s appendix.

Last March, Virginia Fahres, 76, died at Pomona Valley Hospital Medical Center in Pomona after a nurse gave her two drugs, neither of which her doctor had prescribed.

Those incidents were among 1,002 cases of serious medical harm disclosed by California hospitals between July 2007 and May of this year. The disclosures are the first under a state law that requires hospitals to inform health regulators of all substantial injuries to their patients.

Officially called “adverse events,” those accidents are also known as "never events" because they are considered preventable, and many safety experts say they should never happen. California patients are being injured at a rate of about 100 a month, according to data compiled by the state Department of Public Health.

"I think the never events are a wake-up call to everyone about the safety of California hospitals," said Beth Capell, a lobbyist for Health Access California, a consumer group.

Revelations of such errors have led lawmakers and hospital associations in at least seven states to protect patients from having to pay for the cost of care that went awry. In Sacramento, an assemblyman proposed a ban on reimbursing hospitals for the types of injuries tracked by the state. But when lobbyists for doctors and hospitals objected, he scaled it back to cover far fewer errors.

Four million people were admitted to California hospitals last year. State investigators found some errors occurred because hospitals failed to follow safeguards designed specifically to prevent harm.

Last July at UC San Diego Medical Center, a patient died after a nurse incorrectly programmed a medicine pump that then delivered more than twice the appropriate dose of a specialized blood pressure drug. Regulators found that the hospital's administration had been warned earlier by its own safety committee that "errors continue to occur" with that type of pump but had not taken sufficient corrective action, according to a state probe.

UC San Diego officials said they have since held repeat drills with staffers who treat patients with Flolan and examined every step in the process.

Dr. Angela Scioscia, the center's senior medical director, said the public reporting requirement is "a great opportunity to make rapid improvements" because hospitals can learn from one another's problems. "We don't want people to be afraid when they come into hospitals, because they are becoming safer and safer all the time," Scioscia said.

Under the 2006 disclosure law by state Sen. Elaine Alquist (D-Santa Clara), hospitals must inform state regulators of every occurrence of 28 different types of dangerous mistakes. Those include deaths during labor, medication errors, suicide attempts and sexual assaults.

The public health department has until 2015 to begin posting the information on the Internet, although officials said they hope to begin publishing it earlier. The most recent figures available cover the 10 months since July 2007. In that time, 466 patients developed bedsores so severe that the dead skin formed a crater or rotted through to the muscle or bone.

Another 145 patients had foreign objects such as surgical equipment left in their bodies. Thirty-four died while under anesthesia. In 41 surgeries, doctors performed the wrong procedure or operated on the wrong body part or on the wrong patient.

So far, the state Department of Public Health has levied $25,000 fines against 10 hospitals that reported adverse events. Officials said other investigations are still under way.

One hospital, Scripps Memorial in La Jolla, was fined twice for two errors that occurred last November with the same patient. First, as the patient was recovering from surgery, she was given a painkiller that is not supposed to be used after operations. When she went into respiratory arrest, the pharmacist provided a corrective medication at a dose 10 times too weak to be effective.

The patient survived. State investigators discovered that the hospital's pharmacists had not been properly instructed in the use of 10 medications, including the corrective drug, that the hospital stocked for emergencies.

The ventilator error at Stanford's Lucile Packard Children's Hospital occurred because a therapist had assembled the machine by following a diagram that had been drawn backward. Dr. Christy Sandborg, the hospital's chief of staff, said the medical team quickly noticed that the ventilator wasn't working correctly and stopped using it. The child recovered, she said, and the hospital has made changes to prevent future occurrences.

Overcrowded emergency rooms are another factor behind patient injuries. A 2006 study found that California had fewer emergency rooms per resident than any other state.

At Kaiser Foundation Hospital San Jose in March, staffers left a patient waiting in the emergency room for more than an hour after a test showed that his blood sugar was higher than the maximum measurable with a glucometer. The medics determined that he needed immediate care, but all 25 treatment bays were full. He passed out in the waiting room and died from heart failure.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)