To reduce healthcare-associated infections (HAIs) in stand-alone or same-day surgical centers, the HHS Secretary Kathleen Sebelius today announced the availability of up to $9 million in funding from the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) to state survey agencies in 43 states. HAIs are infections some patients acquire when they are in a health care setting such as a hospital or outpatient clinic.

“Because of the Recovery Act, millions of patients who go to stand-alone surgical centers will have greater assurance that they won’t come home with a new infection,” said Health and Human Services’ Secretary Kathleen Sebelius. “Residents in these 43 states will continue to see the benefits from the Recovery Act not only by addressing health care associated infections, but by putting people to work to solve an important issue and improve the quality of life for Americans.”

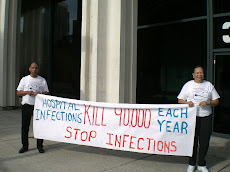

“Healthcare-Associated Infections kill nearly 100,000 people and add an extra $30 billion in healthcare costs every year. But with a little bit of knowledge, and some extra effort, much of that can be prevented. I’m glad to see these funds going to help put people to work combating this tragedy around the country,” said Congressman Dave Obey (D-WI), the Chairman of the House Appropriations Committee, who was a lead author of the Recovery Act and has been an outspoken advocate for efforts to reduce HAIs.

Accredited facilities are surveyed by CMS-approved private accrediting organizations. As part of the new initiative, surveyors in the 43 states will survey approximately 1,300 ambulatory surgical centers (ASCs) across the nation, one-third of the more than 3,800 non-accredited ASCs across the country during the next 12 months. State surveyors will employ a new CMS survey process for ASCs that uses an infection control tool developed in conjunction with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Across the United States, health care services are being shifted to outpatient settings such as ambulatory care facilities, long term care facilities, and free-standing specialty care sites. The number of ASCs participating in Medicare grew from about 3600 in calendar year 2002 to 5200 in early 2009, a 44 percent increase. ASCs account for more than 43 percent of all same-day (ambulatory) surgery in the United States, amounting to about 15 million procedures every year. Typical surgical procedures conducted in ASCs include endoscopies and colonoscopies, orthopedic procedures, plastic/reconstructive surgeries, and eye, foot, and ear/nose/throat surgeries.

HAI outbreaks in outpatient settings continue to occur according to the CDC. In several ASC-related communicable disease outbreaks, failure to employ very basic infection control practices were implicated, leading CMS to identify this as an area for additional oversight.

In the last fiscal year, 12 states volunteered to get a head start on this nationwide effort to reduce healthcare-associated infections in stand-alone or same-day surgical centers by beginning to survey ASCs with funding of nearly $1 million provided through the Recovery Act.

In addition to the funds being made available for the inspection of ASCs, the CDC has also made $40 million available to state public health departments to create or expand state-based HAI prevention and surveillance efforts, and strengthen the public health workforce trained to prevent HAIs.

These funds support activities outlined in HHS’ 2009 Action Plan to Prevent Healthcare-Associated Infections. The plan also establishes national goals, prioritizes recommended clinical practices, and coordinates a national research agenda. Development of this national plan, available at http://www.hhs.gov/ophs/initiatives/hai, is coordinated by HHS’ Office of Public Health and Science, and involves participation from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, CDC, CMS, the Food and Drug Administration, the Indian Health Service, the Health Resources and Services Administration, the National Institutes of Health, the Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology, and other HHS offices, and the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Tuesday, November 10, 2009

Tuesday, November 3, 2009

Where Are the Firing Offenses in Medicine?

Patrick Malone

Posted: October 29, 2009 04:04 PM

The recent news about the two Northwest Airlines pilots whose licenses were revoked, less than a week after they let their plane wander 150 miles off course, raises the question: Where are the firing offenses in medicine?

The pilots injured no passengers, and the event didn't even qualify as a "near miss." But because they egregiously violated safety rules by working on their flight schedules on a laptop in the cockpit, the aviation authorities did not hesitate to pull their licenses.

In the medical industry, by contrast, it is well known that a doctor will lose his or her license for only flagrant patterns of drug or alcohol abuse or other criminal behavior, with a trail of dead and injured patients usually lasting years before the practitioner is finally put out of business.

Medicine's big safety emphasis in recent years has been to create a "no blame" culture that encourages reporting of errors, injuries and "near-misses" by promises of confidentiality and non-punitive action. The idea has been to bring systemic problems out into the open so they can be corrected by implementing "systems" changes, such as checklists to make sure all appropriate steps are taken to prevent infections when inserting catheters into blood vessels.

But what about a doctor who repeatedly puts patients in jeopardy, in small or big ways, by ignoring the rules? Many don't wash their hands routinely when they enter a patient's hospital room, and deadly infections sometimes get spread from patient to patient. Others don't "sign out" their patients at the end of a shift by a person-to-person encounter with the provider taking over.

Some surgeons still won't follow the now routine practice of "signing the site" to prevent wrong-site surgery. If the surgeon is a prominent "feeder" of patients to the hospital, such transgressions can easily be overlooked by administrators who don't want to lose the business. That helps explain why an estimated 4,000 wrong-site surgeries still are performed every year in the United States, more than a decade after the "sign your site" campaign by orthopedic and other surgical specialties.

The good news is that medical safety leaders are starting to call for accountability for rules violations. Dr. Robert Wachter of UC-San Francisco and Dr. Peter Pronovost of Johns Hopkins recently wrote about this in the New England Journal of Medicine. Comparing medicine to aviation (the article was published before the Northwest Airlines incident), they noted: "Every safe industry has transgressions that are firing offenses."

They proposed a short list of offenses in the hospital that should call for suspension of the doctor's practice for one or two weeks: failing to perform hand hygiene, skipping the sign-over to a new provider at the end of a shift, not marking the surgical site, and failing to use a checklist at the start of surgery to make sure everyone in the operating room knows the special needs of the patient. These penalties, they suggested, should only apply after the doctor has failed to respond to an initial warning and counseling.

These modest, tentative steps forward are proposed by the authors to their colleagues as a way of fending off intrusive government regulation. But they also say: "The main reason to find the right balance between 'no blame' and individual accountability is that doing so will save lives."

Amen to that.

Patrick Malone

Attorney and Author of "The Life You Save"

Posted: October 29, 2009 04:04 PM

The recent news about the two Northwest Airlines pilots whose licenses were revoked, less than a week after they let their plane wander 150 miles off course, raises the question: Where are the firing offenses in medicine?

The pilots injured no passengers, and the event didn't even qualify as a "near miss." But because they egregiously violated safety rules by working on their flight schedules on a laptop in the cockpit, the aviation authorities did not hesitate to pull their licenses.

In the medical industry, by contrast, it is well known that a doctor will lose his or her license for only flagrant patterns of drug or alcohol abuse or other criminal behavior, with a trail of dead and injured patients usually lasting years before the practitioner is finally put out of business.

Medicine's big safety emphasis in recent years has been to create a "no blame" culture that encourages reporting of errors, injuries and "near-misses" by promises of confidentiality and non-punitive action. The idea has been to bring systemic problems out into the open so they can be corrected by implementing "systems" changes, such as checklists to make sure all appropriate steps are taken to prevent infections when inserting catheters into blood vessels.

But what about a doctor who repeatedly puts patients in jeopardy, in small or big ways, by ignoring the rules? Many don't wash their hands routinely when they enter a patient's hospital room, and deadly infections sometimes get spread from patient to patient. Others don't "sign out" their patients at the end of a shift by a person-to-person encounter with the provider taking over.

Some surgeons still won't follow the now routine practice of "signing the site" to prevent wrong-site surgery. If the surgeon is a prominent "feeder" of patients to the hospital, such transgressions can easily be overlooked by administrators who don't want to lose the business. That helps explain why an estimated 4,000 wrong-site surgeries still are performed every year in the United States, more than a decade after the "sign your site" campaign by orthopedic and other surgical specialties.

The good news is that medical safety leaders are starting to call for accountability for rules violations. Dr. Robert Wachter of UC-San Francisco and Dr. Peter Pronovost of Johns Hopkins recently wrote about this in the New England Journal of Medicine. Comparing medicine to aviation (the article was published before the Northwest Airlines incident), they noted: "Every safe industry has transgressions that are firing offenses."

They proposed a short list of offenses in the hospital that should call for suspension of the doctor's practice for one or two weeks: failing to perform hand hygiene, skipping the sign-over to a new provider at the end of a shift, not marking the surgical site, and failing to use a checklist at the start of surgery to make sure everyone in the operating room knows the special needs of the patient. These penalties, they suggested, should only apply after the doctor has failed to respond to an initial warning and counseling.

These modest, tentative steps forward are proposed by the authors to their colleagues as a way of fending off intrusive government regulation. But they also say: "The main reason to find the right balance between 'no blame' and individual accountability is that doing so will save lives."

Amen to that.

Patrick Malone

Attorney and Author of "The Life You Save"

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)