Google unveils medical records storage plan

Beth Israel, CVS part of new service

By Jeffrey Krasner

Globe Staff / May 20, 2008

Internet search giant Google Inc. yesterday rolled out its long-awaited Google Health product, which will enable users to upload and store medical records from many sources. Local healthcare companies working with Google on the project include Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston and CVS Caremark of Woonsocket, R.I.

Google said users can enter their personal medical records on a site with individual password protection, giving them a way to view the information from any geographic location. The company said such access is especially useful if a patient becomes ill or is injured far from his or her primary care physician.

"We believe that patients should be the stewards of their own data," said Dr. John Halamka, chief information officer at Beth Israel Deaconess, in a statement.

"Our vision is that [Beth Israel] patients will be able to electronically upload their diagnosis lists, medication lists, and allergy lists in a Google Health account and share that information with healthcare providers who currently don't have access" to Beth Israel's proprietary site, Halamka said.

Many in the healthcare industry consider electronic medical records crucial to reducing the cost of providing healthcare and eliminating medical errors. But the start-up of electronic systems has been painfully slow because few physicians and hospitals can afford to make the investment. Meantime, there are no established standards that would allow data to be shared across different medical record systems.

For Google, the service is part of a plan to boost user loyalty by giving them more reasons to log on to Google sites.

"This really puts the users' records right in their hands," said Marissa Mayer, a Google vice president. "We realize this is just the beginning."

In addition to uploading patient records, patients can also search for medical information, similar to what is offered on the popular website WebMD.

Helena Foulkes, a senior vice president at CVS Caremark, said patients who use in-pharmacy clinics will be able to store the record of their visits on Google Health. That function will be offered first in Tennessee and eventually expand to 500 MinuteClinic locations, she said. The chain is planning to open dozens of such clinics in Massachusetts.

"In today's healthcare environment, information related to an individual's overall health is often fragmented, creating gaps in the availability of data and missed opportunities to coordinate care," said Foulkes in a statement.

Yesterday, Google disclosed a first round of partners in the electronic medical record service. In addition to Beth Israel and CVS Caremark, partners include the Cleveland Clinic, Longs Drug Stores, Medco, and Walgreens Pharmacy. Google will continue to sign up partners to ensure that its users have the broadest possible access to medical information, Mayer said.

Google Health also has a variety of features intended to help users manage their healthcare. They include a link to help users find doctors by location or specialization. Another feature, called a "virtual pillbox," notifies patients when they need to take medications, and it warns of possible drug interactions.

Patient advocates and privacy specialists have expressed concern that despite password protection, sensitive health records stored online could be compromised. In recent years, data breaches have become more common, especially in the retail industry.

Google's new site already faces competition. The Mountain View, Calif., firm's biggest rival, Microsoft Corp., has introduced HealthVault, a similar service that gives users control over who sees their information.

Revolution Health, a start-up backed by former AOL chairman Steve Case, is believed to be working on a service for electronic medical records.

Material from Globe wire services was used in this report. Jeffrey Krasner can be reached at krasner@globe.com.

Friday, May 30, 2008

Wednesday, May 28, 2008

A Patient's Point of View

One of our own Advocate/Survivors Doreen Mulman has had 3 short articles published on Associated Content. Please check out her articles below!

Caring for Your Aging Parent? Please Read This

published on Wed, 28 May 2008 15:10:41 EDThttp://www.associatedcontent.com/article/783843/caring_for_your_aging_parent_please.html

Cleanliness is Next to Impossible published on Mon, 23 Jul 2007 08:41:00 EDThttp://www.associatedcontent.com/article/311453/cleanliness_is_next_to_impossible.html

Necrotizing Fasciitis A Survivors Story

published on Wed, 11 Apr 2007 09:08:00 EDThttp://www.associatedcontent.com/article/190560/necrotizing_fasciitis_a_survivors_story.html

Caring for Your Aging Parent? Please Read This

published on Wed, 28 May 2008 15:10:41 EDThttp://www.associatedcontent.com/article/783843/caring_for_your_aging_parent_please.html

Cleanliness is Next to Impossible published on Mon, 23 Jul 2007 08:41:00 EDThttp://www.associatedcontent.com/article/311453/cleanliness_is_next_to_impossible.html

Necrotizing Fasciitis A Survivors Story

published on Wed, 11 Apr 2007 09:08:00 EDThttp://www.associatedcontent.com/article/190560/necrotizing_fasciitis_a_survivors_story.html

Tuesday, May 27, 2008

MRSA Survivors Network

MRSA Survivors Network launches their new web site (http://www.mrsasurvivors.org/) and blog. MSN is the first consumer organization in the U.S. to raise the alarm about MRSA and healthcare-acquired infections. MSN has been the catalyst for prevention of MRSA infections by initiating groundbreaking legislation mandating MRSA screening and reporting.

The new web site will cover the latest issues concerning MRSA and is both consumer and healthcare professional driven to change the course of this disease.

For more information contact Jeanine Thomas at: jthomas@mrsasurvivors.org

The new web site will cover the latest issues concerning MRSA and is both consumer and healthcare professional driven to change the course of this disease.

For more information contact Jeanine Thomas at: jthomas@mrsasurvivors.org

Tuesday, May 20, 2008

Doctors On The Take

http://www.twincities.com/ci_9316658?IADID=Search-www.twincities.com-www.twincities.com

St. Paul Pioneer Press

Part III in our series

Critics say drug firms' payments to doctors are conflict of interest

What they spend: A look at drug company spending in Minnesota ― on top specialties and select psychiatrists.

By Jeremy Olson and Paul Tosto Pioneer Press

Article Last Updated: 05/20/2008 07:25:43 AM CDT

Drug companies have given $88 million in gifts, grants and fees to Minnesota doctors and caregivers since 2002, according to state payment records, including $782,000 to the two University of Minnesota psychiatrists who oversaw Dan Markingson's participation in a clinical drug trial.

A lawsuit over Markingson's suicide, which happened during the drug trial, accused Dr. Stephen Olson and Dr. S. Charles Schulz, chairman of the U's psychiatry department, of coercing the schizophrenic Markingson into the study.

The lawsuit, brought by Markingson's mother, Mary Weiss, charged that the doctors were under pressure to recruit patients such as Markingson to maximize payments from AstraZeneca and gain prestige by participating in the drug company's national study.

Both doctors said in court depositions that their roles were appropriate and that the money didn't influence their decisions over Markingson ― including when his mother argued that he wasn't getting better in the study and should be withdrawn.

Schulz was dismissed from the lawsuit in February; Olson settled this spring for an amount a university official described as little more than court costs. Federal reviews of the death didn't result in any penalties against the doctors or the university.

The case nonetheless offered an inside look at the kind of financial payments to doctors that some health policy experts and congressional representatives say should be restricted or at least fully disclosed to the public.

It also scrutinized the ethics of drug company funding of research ― something that has received less public attention and criticism than the free lunches, dinners and trips that drug companies have provided to doctors to promote their drugs.

Markingson, 27, killed himself May 8, 2004, in the bathroom of a West St. Paul halfway house. He had been enrolled for more than five months in the university's "CAFE" study, which compared three antipsychotic drugs.

Weiss sued the university and the psychiatrists. In an interview, she said doctors have a conflict of interest when they are financially benefiting from studies and caring for patients in those studies at the same time.

"I think they lose sight that these are people," she said, "not their own special little guinea pigs."

Minnesota is unique in requiring drug companies to report how much money they give to each doctor, but the reporting system has limitations. It doesn't always distinguish between money for a doctor's travel expenses and money for a research trial, nor does it distinguish money that was in a doctor's name but was passed directly to a research institution.

U.S. Sen. Chuck Grassley, R-Iowa, is urging a national reporting system. Grassley held a hearing last year in which two doctors said their colleagues have become trapped by the lures and pressures of drug company money.

"Physicians face a difficult choice," testified Dr. Greg Rosenthal, an Ohio eye specialist. "One path is to go along. With drug company money, you can increase your income, prestige, build your practice or fund a department, research or professorships. The middle ground is to simply look away. The hard choice is to fight back."

Olson received $220,000 from six companies since 2002, including $149,000 from AstraZeneca, according to the state records. Schulz received $562,000, including $112,000 as a researcher and consultant to AstraZeneca.

Olson said his AstraZeneca money went straight to the U but did support his salary. Markingson's full participation in the yearlong study meant up to $15,000 for the university.

The amounts aren't unusual, according to the payment records collected by the Minnesota Board of Pharmacy. The records, which were updated this month to include 2007 figures, show 167 Minnesota doctors who have received $100,000 or more since 2002. One in four psychiatrists has received funding from pharmaceutical companies, averaging about $50,000 over the six years.

Greater awareness of drug company payments has prompted tighter rules among some Minnesota health care organizations. The Mayo Clinic prohibits its doctors from being paid by drug companies to serve on their speaker's bureaus. Doctors in speaker's bureaus give lectures to other doctors about the company's medications.

The St. Mary's clinic system in Duluth recently banned pens, mugs or other freebies bearing drug company logos.

There have been fewer steps to restrict drug company funding of research, though most medical journals long ago required doctors to disclose the funding source of any research results they publish. Some health officials are now questioning the drug companies' use of "ghostwriters" to revise articles about research results to promote the drugs they sell.

Many universities view industry-sponsored research as a necessity amid tightening state and federal science budgets. Drug company funding makes up less than 7 percent of the psychiatry department budget at the University of Minnesota, but Schulz said it is needed as the U tries to move up the list of top-funded U.S. research institutions.

Since Olson was recruited in 2001 to boost the university's expertise in schizophrenia, he has led the U's efforts in three drug trials funded by AstraZeneca. He also took part in the federally funded "CATIE" trial, which suggested that older antipsychotic drugs were as effective as AstraZeneca's Seroquel and other newer drugs.

A growing body of research suggests that drug company money has an influence on study outcomes. One analysis found that industry-funded research was four to five times more likely to produce positive outcomes for a paying company's drug than federally funded research. A report last year found that drug company-funded studies of cholesterol medications were much more likely to produce results that favored their own drugs as well.

The CAFE results didn't show that AstraZeneca's Seroquel offered much benefit over two competitors ― Zyprexa and Risperdal. Patients gained control over schizophrenic symptoms and tended to stop taking the medications at the same rate, regardless of which drug they took. The level of unhealthy weight gain was comparable, too, albeit slightly higher among the Zyprexa patients.

Weiss sued AstraZeneca as well, though the company also was dismissed from the lawsuit. Her attorneys argued that AstraZeneca's goal with the CAFE study was to gain a marketing edge and that the company used selective information from the study to promote Seroquel.

The attorneys cited internal documents, which have been sealed under court order, in which AstraZeneca discussed its use of ghostwriters and strategies to present CAFE results in a way that "sells" Seroquel.

AstraZeneca declined to discuss documents from the case, but brand corporate affairs manager Abigail Baron said the company's financial arrangements with doctors are necessary to improve health through drug discovery.

"That mission cannot be fulfilled," she said, "without close partnership with those on the front lines of patient care and ... research."

Jeremy Olson can be reached at 651-228-5583 or jolson@pioneerpress.com. Paul Tosto can be reached at 651-228-2119 or ptosto@pioneerpress.com.

How Much?

Visit our database of drug company payments to Minnesota doctors Related to This series

Patient's suicide raises questions

Dan Markingson had delusions. His mother feared that the worst would happen. Then it did.

St. Paul Pioneer Press

Part III in our series

Critics say drug firms' payments to doctors are conflict of interest

What they spend: A look at drug company spending in Minnesota ― on top specialties and select psychiatrists.

By Jeremy Olson and Paul Tosto Pioneer Press

Article Last Updated: 05/20/2008 07:25:43 AM CDT

Drug companies have given $88 million in gifts, grants and fees to Minnesota doctors and caregivers since 2002, according to state payment records, including $782,000 to the two University of Minnesota psychiatrists who oversaw Dan Markingson's participation in a clinical drug trial.

A lawsuit over Markingson's suicide, which happened during the drug trial, accused Dr. Stephen Olson and Dr. S. Charles Schulz, chairman of the U's psychiatry department, of coercing the schizophrenic Markingson into the study.

The lawsuit, brought by Markingson's mother, Mary Weiss, charged that the doctors were under pressure to recruit patients such as Markingson to maximize payments from AstraZeneca and gain prestige by participating in the drug company's national study.

Both doctors said in court depositions that their roles were appropriate and that the money didn't influence their decisions over Markingson ― including when his mother argued that he wasn't getting better in the study and should be withdrawn.

Schulz was dismissed from the lawsuit in February; Olson settled this spring for an amount a university official described as little more than court costs. Federal reviews of the death didn't result in any penalties against the doctors or the university.

The case nonetheless offered an inside look at the kind of financial payments to doctors that some health policy experts and congressional representatives say should be restricted or at least fully disclosed to the public.

It also scrutinized the ethics of drug company funding of research ― something that has received less public attention and criticism than the free lunches, dinners and trips that drug companies have provided to doctors to promote their drugs.

Markingson, 27, killed himself May 8, 2004, in the bathroom of a West St. Paul halfway house. He had been enrolled for more than five months in the university's "CAFE" study, which compared three antipsychotic drugs.

Weiss sued the university and the psychiatrists. In an interview, she said doctors have a conflict of interest when they are financially benefiting from studies and caring for patients in those studies at the same time.

"I think they lose sight that these are people," she said, "not their own special little guinea pigs."

Minnesota is unique in requiring drug companies to report how much money they give to each doctor, but the reporting system has limitations. It doesn't always distinguish between money for a doctor's travel expenses and money for a research trial, nor does it distinguish money that was in a doctor's name but was passed directly to a research institution.

U.S. Sen. Chuck Grassley, R-Iowa, is urging a national reporting system. Grassley held a hearing last year in which two doctors said their colleagues have become trapped by the lures and pressures of drug company money.

"Physicians face a difficult choice," testified Dr. Greg Rosenthal, an Ohio eye specialist. "One path is to go along. With drug company money, you can increase your income, prestige, build your practice or fund a department, research or professorships. The middle ground is to simply look away. The hard choice is to fight back."

Olson received $220,000 from six companies since 2002, including $149,000 from AstraZeneca, according to the state records. Schulz received $562,000, including $112,000 as a researcher and consultant to AstraZeneca.

Olson said his AstraZeneca money went straight to the U but did support his salary. Markingson's full participation in the yearlong study meant up to $15,000 for the university.

The amounts aren't unusual, according to the payment records collected by the Minnesota Board of Pharmacy. The records, which were updated this month to include 2007 figures, show 167 Minnesota doctors who have received $100,000 or more since 2002. One in four psychiatrists has received funding from pharmaceutical companies, averaging about $50,000 over the six years.

Greater awareness of drug company payments has prompted tighter rules among some Minnesota health care organizations. The Mayo Clinic prohibits its doctors from being paid by drug companies to serve on their speaker's bureaus. Doctors in speaker's bureaus give lectures to other doctors about the company's medications.

The St. Mary's clinic system in Duluth recently banned pens, mugs or other freebies bearing drug company logos.

There have been fewer steps to restrict drug company funding of research, though most medical journals long ago required doctors to disclose the funding source of any research results they publish. Some health officials are now questioning the drug companies' use of "ghostwriters" to revise articles about research results to promote the drugs they sell.

Many universities view industry-sponsored research as a necessity amid tightening state and federal science budgets. Drug company funding makes up less than 7 percent of the psychiatry department budget at the University of Minnesota, but Schulz said it is needed as the U tries to move up the list of top-funded U.S. research institutions.

Since Olson was recruited in 2001 to boost the university's expertise in schizophrenia, he has led the U's efforts in three drug trials funded by AstraZeneca. He also took part in the federally funded "CATIE" trial, which suggested that older antipsychotic drugs were as effective as AstraZeneca's Seroquel and other newer drugs.

A growing body of research suggests that drug company money has an influence on study outcomes. One analysis found that industry-funded research was four to five times more likely to produce positive outcomes for a paying company's drug than federally funded research. A report last year found that drug company-funded studies of cholesterol medications were much more likely to produce results that favored their own drugs as well.

The CAFE results didn't show that AstraZeneca's Seroquel offered much benefit over two competitors ― Zyprexa and Risperdal. Patients gained control over schizophrenic symptoms and tended to stop taking the medications at the same rate, regardless of which drug they took. The level of unhealthy weight gain was comparable, too, albeit slightly higher among the Zyprexa patients.

Weiss sued AstraZeneca as well, though the company also was dismissed from the lawsuit. Her attorneys argued that AstraZeneca's goal with the CAFE study was to gain a marketing edge and that the company used selective information from the study to promote Seroquel.

The attorneys cited internal documents, which have been sealed under court order, in which AstraZeneca discussed its use of ghostwriters and strategies to present CAFE results in a way that "sells" Seroquel.

AstraZeneca declined to discuss documents from the case, but brand corporate affairs manager Abigail Baron said the company's financial arrangements with doctors are necessary to improve health through drug discovery.

"That mission cannot be fulfilled," she said, "without close partnership with those on the front lines of patient care and ... research."

Jeremy Olson can be reached at 651-228-5583 or jolson@pioneerpress.com. Paul Tosto can be reached at 651-228-2119 or ptosto@pioneerpress.com.

How Much?

Visit our database of drug company payments to Minnesota doctors Related to This series

Patient's suicide raises questions

Dan Markingson had delusions. His mother feared that the worst would happen. Then it did.

Monday, May 19, 2008

Let's Set Our Standards High!

Zero Tolerance for Infections: A Winning Strategy

Kelly M. Pyrek01/24/2008

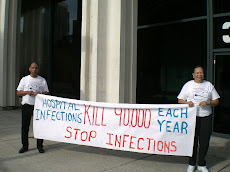

“Zero tolerance” is quickly becoming the new watchword in infection prevention, as the concept of striving for zero infiltrates U.S. hospital staffs as they strive to meet new pay-for-performance mandates from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), this fall and to address healthcare-associated infections (HAIs) as “never-events.”

How did we get here? The data tell the clearest story. Approximately 2 million healthcare-associated infections (HAIs) occur annually in U.S. healthcare facilities, lead to 60,000-90,000 deaths and cost anywhere from $17 billion to $29 billion. Five percent to 15 percent of all hospitalized patients in developing countries develop an HAI; more than three-quarters of these infections are urinary tract infections, bloodstream infections (BSIs), pneumonia or surgical site infections (SSIs).1 Not only are patients sicker, pathogens are becoming stronger in their ability to shrug off microbicides, making for a potential train wreck of epic proportions unless our course is diverted.

At no time in history have healthcare institution infection prevention and control programs been more critical than they are today, and they are being supplemented by collaboratives and initiatives from public- and private-sector groups agitating for change and a recognition that something must be done to address increasing prevalence of hospital- and community-acquired infections. The Joint Commission has long required its accredited facilities to observe its patient safety goals, including preventing infections. It has been joined in recent years by a number of other agencies hoping to curb infections, including the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) and the Surgical Care Improvement Project (SCIP), as well as consumer watchdog groups such as Consumers Union and the Committee to Reduce Infection Deaths (RID). The call for public disclosure of infection rates is sweeping the country, and the MRSA scare several months ago has capitulated the angst Americans are feeling over opportunistic infections.

Infections are now on the radar of hospital administrators thanks to the aforementioned pay-for-performance mandates issued by CMS which is clamping down Oct. 1 on hospital reimbursement for complications relating to infections. Infection control practitioners (ICPs), who have long been the front-line defenders against infections and adverse events, find themselves needing to bone up on risk management principles and fiscal concepts as they attempt to tally up the high costs of infections and make the business case for infection prevention.

In the midst of this turning tide are the other healthcare workers (HCWs) responsible for providing medical and surgical care to patients and who have been blamed as the guilty party for ignoring infection prevention principles and best practices — all in a daily rush to do their jobs amidst staffing and resource shortages triggered by razor-thin hospital budgets that keep getting thinner. Although healthcare workers know what to do, they don’t always do it.

Behavior modification and cultural change is the answer, as is a call for a transition from benchmarking to zero tolerance. But there are degrees of behavior modification initiatives, from the warm and fuzzy, to the punitive and everything in between. Denise M. Murphy, MPH, BSN, RN, CIC, president of the Association for Professionals in Infection Control and Epidemiology (APIC) and the chief patient safety and quality officer at Barnes-Jewish Hospital in St. Louis, alludes to a recent meeting of public health groups that discussed zero tolerance and concerns regarding the potential for a punitive response if hospitals set the goal at zero. “This could come from healthcare executives, or even the public, when an infection occurred despite compliance with known prevention measures and where no breakdown in safe practice was found,” Murphy says. “So we settled on language stating that we’re ‘targeting zero.’ One means of eliminating as many HAIs as possible will be zero tolerance for not adhering to infection prevention measures and broken systems that lead to harm.”2

Without a national standard or model, institutions are left to decide a course of action on their own. Either way, zero tolerance is taking on new urgency as healthcare institutions decide to take a stronger stance against the number of infections previously thought to be preventable. In a 2006 story on hospital infections, Washington Post reporter Christopher Lee quotes David B. Nash, chairman of the Department of Health Policy at Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia, as remarking, “The new wave of research is showing that our previous expectations around what was preventable underestimated what we could actually achieve. We can prevent more infections than we thought before. Lots of hospitals are striving to get to zero.”3

Noted infection prevention expert William Jarvis, MD, of Jarvis and Associates based in Hilton Head, S.C., alludes to the struggle over just how many infections are preventable. “There has been much debate over the years,” says Jarvis, who spent 23 years at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). “When I was at the CDC and I would say one-third of infections are preventable, a number of people would argue, ‘that’s way too high, you can’t do that.’ But with various collaboratives and other interventions in the last five to eight years, what we have seen is that a much higher proportion of infections is preventable, whether we are talking about surgical site infections, ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP), central line-associated bloodstream infections, or even methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infections. Interventions have prevented well over 50 percent and in some cases even 80 percent and 90 percent of infections, so now if we can get clinicians to implement the evidence-based recommendations that we know work, we will be very successful at preventing many infections.”

Jarvis continues, “Will we reach zero? No, but the attitude that I think we are moving toward, is one where clinicians don’t see these infections as inevitable. There are very sick patients who need a lot of invasive devices and procedures, so they are going to get infections. We need the attitude of trying to preventing all infections, and if one occurs, investigating to see what went wrong.”

Getting to zero is the basis of the “zero tolerance” of infections movement that has arisen in the last several years, promulgated by APIC. Murphy notes, “Why is the phrase ‘zero tolerance’ getting so much hype, and why should we be shaping what zero tolerance means in terms of infection prevention? Because too many people are still dying or being harmed by HAIs. We know the numbers because we compile them, but every number is someone’s loved one. Keeping people safe is the reason we do what we do — not rates. But rates and numbers measure our success so the goal must be elimination of HAIs, the metric or target must be zero. Zero is often possible. Many APIC members and their teams have set zero as the target and achieved that goal. They are truly saving lives.”2

Murphy says at that meeting among public health groups where zero tolerance was discussed, the concept was formally defined as “a culture, a goal, an attitude, and a commitment.” Murphy adds, “Infection prevention is no longer getting to a benchmark and stopping there. Zero tolerance means we must keep going, targeting zero. John Jernigan from CDC said, ‘In public health we talk about elimination all the time, about eliminating TB and other infectious diseases. So why wouldn’t we set a theoretical goal of zero even if we can’t prevent every infection because we cannot control all risk factors?’ Zero tolerance means treating every infection as if it should never happen, but when it does, we investigate the root cause. Finally, it means holding everyone accountable for HAIs, not just the ICPs.”2

Zero tolerance is creating a new infrastructure for infection prevention that includes other effective tools such as evidence-based interventions in the form of bundles. Jarvis writes, “… no single intervention prevents any HAI; rather a ‘bundle’ approach, using a package of multiple interventions based on evidence provided by the infection control community and implemented by a multidisciplinary team is the model for successful HAI prevention.” But an increasing number of researchers are acknowledging that addressing the behavioral aspects of infection prevention compliance is essential to fighting infections.1

Aboelela and colleagues4 note that attempts to address the growing problem of HAIs and their impact on healthcare systems have historically relied on infection control policies that recommend good hygiene through Standard Precautions. But they emphasize, “In order for infection control strategies to be effective, however, HCWs’ behavior must be congruent with these policies.” Aboelela and colleagues conducted a systematic review to evaluate studies testing the effectiveness of interventions aimed at changing HCWs’ behavior in reducing HAIs. Of 33 published studies, four studies reported significant reductions in HAI or colonization rates. Behavioral interventions used in these studies included an educational program, the formation of a multi-disciplinary quality improvement team, compliance monitoring and feedback, and a mandate to sign a hand hygiene requirement statement. In all 33 studies, bundles of two to five interventions were employed, making it difficult to determine the effectiveness of individual interventions. The researchers noted, “The usefulness of ‘care bundling’ has recently been recognized and recommended by the Institute for Healthcare Improvement. Considering the multifactorial nature of the HAI problem and the logistical and ethical difficulties of applying the randomized clinical trial approach to infection control research, it may be necessary to study interventions as sets of practices.”4

These practices — and their payoffs in fighting infections — have traditionally been evaluated through benchmarking activities. The one challenge with infection prevention is that much of it has been based on benchmarking among U.S. hospitals; Jarvis says that national benchmarking can be a less-than-ideal representation of infection rates across the country because it can be skewed toward large academic or teaching hospitals. “There has been this benchmarking mentality where people would look at their infection rate and then look at the CDC’s surveillance rates within the National Nosocomial Infections Surveillance System (NNIS), without realizing that they only really account for a small minority of hospitals in that system,” Jarvis explains. “Secondly, hospitals having less than 100 beds are not even allowed in that system, even though the average U.S. hospital is less than 100 beds. That means the majority of U.S. hospitals weren’t represented in that system — it was mostly academic centers that were providing the benchmarks. Everybody would look at that and say, ‘Well, if my infection rate is at or below the median of the NNIS system then I am fine, I don’t need to do anything.’”

Jarvis explains further, “The debate goes back to the mid-1970s, when the CDC conducted its landmark SENIC Project, the study of the efficacy of nosocomial infection control programs, which was a retrospective medical record chart review, and it was the first time that infection control was documented in a valid, scientific way to be cost effective and to prevent infections.” The SENIC Project was designed with three primary objectives: to determine whether (and, if so, to what degree) the implementation of infection surveillance and control programs (ISCPs) has lowered the rate of nosocomial infection, to describe the current status of ISCPs and infection rates, and to demonstrate the relationships among characteristics of hospitals and patients, components of ISCPs, and changes in the infection rate.

“At the time, no one really had a sense of what percent of infections were preventable,” Jarvis says. “Researchers conducted chart reviews and interviews about infection control programs and then they made estimates based upon the data they collected. They looked at which hospitals had epidemiologists and which had infection control professionals, how many did they have, what did they do, and then looked at programs in hospitals with lower infection rates compared to those who had higher infection rates and then made an estimate that in general, about one-third of HAIs were preventable. So it really was more of a guesstimate.”

In a 2007 white paper1 Jarvis underscored that benchmarking is inadequate and a culture of zero tolerance is required, as is a culture of accountability and administrative support. “In order to reach the goal of zero infections, hospitals need accountability,” Jarvis says. “In many U.S. hospitals, infection control programs are not well supported by administrators because they are not revenue-generating departments. Imagine a CEO at a hospital; two people from his facility offer him an option for the future; the first is the facility’s ICP. She says, ‘We can prevent many of these infections but we need more personnel. I’d like to hire one or two additional infection control personnel.’ She’s probably talking about less than $150,000 a year in salary costs, and you can prevent five infections. The next person who comes in is the chief of cardiovascular surgery who says, ‘I’d like to build a new operating room because I can do two or three coronary artery bypass procedures at $200,000 to $500,000 a pop.’ For the CEO, the decision is kind of a ‘duh!’ as to which decision he is going to make — she is always going to build the operating room.”

Jarvis continues, “Hospital CEOs and administrators must understand the importance of infection prevention and its impact on patient safety. They must realize it’s not about lip service, it’s about taking action and spending money to get to zero. There are a number of things happening that are getting the attention of hospital administrators, including CMS mandates, public reporting and other legislation at the state level. These things are bringing infections into the open, so hospital administrators are starting to see the light.”

If administrators are to see improvements in their facilities and not lose revenue from CMS, they are going to have to resolve the aforementioned issue of behavioral modification among clinicians. There are several classical battles being waged between ICPs and clinicians regarding compliance issues. One of the most enduring examples is that of hand hygiene compliance, which notoriously hovers around 30 percent to 40 percent. Studies indicate that HCWs wash their hands just one-third to one-half as often as they should.

Whitby and colleagues5 observe, “Although HCW compliance with handwashing guidelines is a cornerstone of ideal infection control practice, the rate of such compliance has proved to be abysmal.” For years, researchers have studied various interventions to discover how to improve HCWs’ knowledge of and compliance with handwashing guidelines and then reinforcing these practices. Whitby and colleagues note that “until recently, none have engendered evidence of sustained improvement during a protracted period.”

In 2000, two studies provided hope that handwashing practice could be improved. Pittet and colleagues.6 demonstrated that handwashing compliance among nurses at the University of Geneva hospitals increased to 66 percent during a 48-month period thanks to a number of interventions likely to affect HCW behavior including the provision of an alcohol-based hand rub designed to reduce the time taken and the inconvenience associated with handwashing. Larson and colleagues.7 described a significant increase in handwashing compliance that was sustained for 14 months in a Washington, D.C. teaching hospital. Their program attempted to induce organizational cultural change toward optimal hand hygiene, with senior administrative and clinical staff overtly promoting the handwashing program. Whitby and colleagues write, “Handwashing as a practice is a globally recognized phenomenon; however, the inability to motivate HCW compliance with handwashing guidelines suggests that handwashing behavior is complex. Human behavior is the result of multiple influences from our biological characteristics, environment, education, and culture.”5

For their study, Whitby and colleagues used the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB), explaining that with regard to handwashing, TPB is “predicated on a person’s acceptance that the immediate cause of handwashing is their antecedent intention to wash their hands. The intention to perform a given behavior is predicted directly, although to differing degrees, by three variables: attitude (a feeling that the behavior is associated with certain attributes or outcomes that may or may not be beneficial to the individual), subjective norms (a person’s perception of pressure from peers and other social groups), and perceived behavioral control (a person’s perception of the ease or difficulty in performing the behavior). These variables are predicted by the strength of the person’s beliefs about the outcomes of the behavior, normative beliefs (which are based on a person’s evaluation of the expectations of peers and other social groups), and control beliefs (which are based on a person’s perception of their ability to overcome obstacles or to enhance resources that facilitate or obstruct their undertaking of the behavior).

Whitby and colleagues’ investigations focused on elucidating and determining the origin of the behavioral determinants of handwashing in nurses in the healthcare setting. According to the researchers, handwashing was perceived by the study subjects foremost as a mechanism of self protection against harmful organisms. Handwashing behavior was also influenced by the appearance of their hands. Nurses recognized that handwashing played an integral role in the removal of microbes and the prevention of their transfer, and described the practice as unconscious and habitual, rather than as a thoughtful action associated with particular occasions.

Whitby and colleagues reported that although nurses appeared to believe that they habitually washed their hands without thinking about it, a number of factors appeared to affect the importance that they placed on handwashing in the healthcare setting, including the condition of their patients, the extent of patient contact, their assessment of the task involving a patient, and workload. They write, “Nurses believed that patients are a potential reservoir of infection because patients have little understanding of infection transmission. Nurses assessed the risk of infection due to contact with individual patients on the basis of several criteria, including the patient’s diagnosis, physical appearance, and perceived general cleanliness; visibility of the patient’s body fluids; and the patient’s age. An assessment was made in terms of the degree of ‘dirtiness’ or the lack of ‘cleanliness’ of a patient. Handwashing was not always considered to be essential for certain types of physical contact with patients. Tasks that require non-intimate touching of a patient or use of inanimate objects were less likely to be considered important motivating factors for handwashing, compared with tasks involving more-prolonged physical contact. In parallel with the nurse’s assessment of the task involving a patient, nurses judged the level of ‘dirtiness’ of the actual task. This assessment resulted in nursing staff feeling compelled to wash their hands if their hands were visibly contaminated, moist or gritty, or touched axillae, genitals or the groin. Nurses reported that, when under time constraints, they used physical and task assessments to determine the necessity of handwashing. However, nurses always felt compelled to wash hands after performing tasks they considered to be ‘dirty.’”5

Whitby and colleagues point out that attitudes toward physical contamination, such as fecal material, is consistent with a hypothesis developed by Curtis and Biran, who argue that the human emotion of “disgust” is an evolutionary protective response to environmental factors that may pose a risk of infection.8 Whitby and colleagues note, “This response may be mirrored in the way that nurses make judgments about the potential risk for infection that contact with a patient may pose. Their assessment of the need to wash hands was strongly influenced by the emotional concepts of ‘dirtiness’ and ‘cleanliness.’”5 Whitby and colleagues say their data suggest that an individual’s handwashing behavior is not a homogenous practice but falls into two broad categories. The first category, “inherent handwashing practice,” occurs when hands are visibly soiled or feel sticky or gritty and requires hand cleansing with water. The second category is “elective handwashing behavior,” which does not trigger an intrinsic response with an immediate desire to wash one’s hands; it represents to the nurse an elective opportunity for handwashing. Whitby and colleagues also indicate that because of perceived time constraints, nurses appear to act through a self-developed “hierarchy of risk” to determine when handwashing was necessary, thus ranking their opportunities for handwashing. When pressed for time, nurses assign lower priority to washing their hands than they do to other more urgent tasks.5

“A major component of zero tolerance is accountability,” Jarvis emphasizes. “In general, healthcare professionals are not taught about infection prevention in medical school or nursing school. We are not reaching them at a time when we could tell them this is critical to saving lives, so as a result many of them come out of training not thinking this is very important. Also, many clinicians think infection control is the infection control department’s job, not theirs. The fact is, infection control personnel should be the hospital’s consultants — they have the knowledge of what can and should be done to prevent infections, but they are not the people putting in IV lines or putting people on ventilators, they’re not the ones not doing hand hygiene, and that’s where accountability comes in. A number of large healthcare systems are taking a very aggressive approach against MRSA because the data show we can prevent many HAIs including MRSA. I was intrigued by a very large healthcare system whose CEO contacted the CEOs of each of the hospitals and told them in 2008 their yearend bonuses would be dependent upon how well they prevented MRSA infections. If you don’t think that’s going to make clinicians have some accountability, you’re nuts. The CEOs at each of those hospitals are going to ensure their clinicians are accountable for infections because it will impact the CEOs’ pockets.”

Jarvis continues, “Behavioral changes are key. One of the biggest challenges we have had in infection control is getting clinicians to do proper hand hygiene, and we have to admit that those of us in healthcare are absolutely atrocious at achieving behavioral change. If you look at changes in behavior, whether it’s wearing seatbelts or helmets or not smoking, we don’t change our behavior because of any kind of educational program, it’s because we have to obey the law — a law is passed and you have to wear a seatbelt or you get fined. We are very poor in our understanding of the capability to change HCW behavior. It’s why hospital CEOs and administrators must move that accountability down to unit directors. A good example of this is a surgical intensive care unit. We commonly see surgeons do a tremendous job of hand hygiene before they go into the OR; they gown and glove and mask and cap, and then they scream at anyone who violates infection control in the OR. Then they finish surgery, walk out of the OR, walk into the ICU and go from patient to patient to patient and don’t do hand hygiene. That kind of behavior must become a violation in the eyes of the unit director, who warns you one time and the second time you are out of there.

“It requires a tremendous change in our culture,” Jarvis says. “For example, there are no data to show that gowning and gloving and masking in the OR actually reduces infections — there has never been a randomized controlled trial. Yet if I went into any U.S. hospital wearing the clothes I have on right now and said I want to do surgery, there would be at least four people who would tackle me before I got to the OR — even though there are no data to suggest there would be a negative impact on patients if I did that. But it’s a cultural expectation in healthcare, and I think we have to change that culture throughout our hospitals with respect to infection prevention, where everyone is expected to do the right thing. And when they’re not, others tell them they must.”

APIC provided a startling insight late last year when it released findings from a non-scientific poll of ICPs asking them about changes made in their hospitals to better address MRSA infection rates.9 This poll came on the heels of APIC’s MRSA prevalence study, written by Jarvis. “APIC’s follow-survey showed that approximately 50 percent of the ICPs who responded to the poll said they had not done more to fight MRSA because they were not given the resources they needed by their hospital administration,” Jarvis says. “I think that will continue to be an issue and it’s only through public reporting and increasing state legislation that infection control program resourcing issues will be acknowledged. With CMS penalizing hospitals on one side and legislation on the other, the two of them are going to start squeezing, and hopefully this pressure will yield results in improved resourcing, reduced infections and the kind of healthcare all of us should expect.”

Murphy provides a 10-point plan10 for getting to zero:

1. Educate all healthcare providers about infection prevention

2. Educate hospital administration about infection prevention

3. Challenge HCWs to lead the charge against HAIs

4. Influence and educate stakeholders

5. Educate the community about infection prevention

6. Use and share meaningful infection data

7. Automate more tasks in infection prevention so more time is spent on education efforts

8. Learn how to make the business case for infection prevention

9. Develop strategic partnerships

10. Keep the patient at the center of all infection prevention efforts Murphy notes,

“What else do we need to do to get to zero? We need each other. ICPs worldwide need to persist, and together we can eliminate HAIs. We can broaden the range of what’s preventable. By partnering with patients and their families and healthcare teams, with researchers, educators, standards and law makers, industry, and innovators, we can work to establish a reliable system that prevents harm from infection. We must continue to negotiate effectively to get resources needed to prevent HAIs, and then we can ‘pay it forward’ to our patients and their families.2

APIC recently announced the launch of its “Targeting Zero” Initiative. For more details, go to: http://www.infectioncontroltoday.com/hotnews/targeting-zero-initiative-launched.html

References

1. Jarvis W. The United States approach to strategies in the battle against healthcare-associated infections, 2006: transitioning from benchmarking to zero tolerance and clinician accountability. Journal of Hospital Infection. Vol. 65. Pages 3-9.

2. Murphy DM. Go for zero then pay it forward. APIC News. Fall 2007.

3. Lee C. Studies: Hospitals Could do More to Avoid Infections. The Washington Post. Nov. 21, 2006.

4. Aboelela SW, Stone PW and Larson EL. Effectiveness of bundled behavioral interventions to control healthcare-associated infections: a systematic review of the literature. Journal of Hospital Infection. Vol. 66, No. 2. Pages 101-108 June 2007.

5. Whitby M, McLaws ML, Ross MW. Why healthcare workers don’t wash their hands: A behavioral explanation. Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology. Vol. 27, No. 5. May 2006.

6. Pittet D, Hugonnet S, Harbarth S, et al. Effectiveness of a hospital-wide program to improve compliance with hand hygiene. Lancet 2000; 356: 1307-1312.

7. Larson EL, Early E, Cloonan P, Sugrue S, Perides M. An organizational climate intervention associated with increased handwashing and decreased nosocomial infection. Behav Med 2000; 26:14-22.

8. Curtis V, Biran A. Dirt, disgust, and disease: is hygiene in our genes? Perspect Biol Med 2001; 44:17-31.

9. APIC. Survey Finds U.S. Healthcare Facilities Not Doing Enough to Curb MRSA. Accessed at: http://www.infectioncontroltoday.com/hotnews/curbing-mrsa.html

10. Time to come clean. Hospital Management. March 2007. Accessed at: http://www.hospitalmanagement.net/features/feature977/

var loc = window.location.pathname;var nt=String(Math.random()).substr(2,10);document.write ('');

Kelly M. Pyrek01/24/2008

“Zero tolerance” is quickly becoming the new watchword in infection prevention, as the concept of striving for zero infiltrates U.S. hospital staffs as they strive to meet new pay-for-performance mandates from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), this fall and to address healthcare-associated infections (HAIs) as “never-events.”

How did we get here? The data tell the clearest story. Approximately 2 million healthcare-associated infections (HAIs) occur annually in U.S. healthcare facilities, lead to 60,000-90,000 deaths and cost anywhere from $17 billion to $29 billion. Five percent to 15 percent of all hospitalized patients in developing countries develop an HAI; more than three-quarters of these infections are urinary tract infections, bloodstream infections (BSIs), pneumonia or surgical site infections (SSIs).1 Not only are patients sicker, pathogens are becoming stronger in their ability to shrug off microbicides, making for a potential train wreck of epic proportions unless our course is diverted.

At no time in history have healthcare institution infection prevention and control programs been more critical than they are today, and they are being supplemented by collaboratives and initiatives from public- and private-sector groups agitating for change and a recognition that something must be done to address increasing prevalence of hospital- and community-acquired infections. The Joint Commission has long required its accredited facilities to observe its patient safety goals, including preventing infections. It has been joined in recent years by a number of other agencies hoping to curb infections, including the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) and the Surgical Care Improvement Project (SCIP), as well as consumer watchdog groups such as Consumers Union and the Committee to Reduce Infection Deaths (RID). The call for public disclosure of infection rates is sweeping the country, and the MRSA scare several months ago has capitulated the angst Americans are feeling over opportunistic infections.

Infections are now on the radar of hospital administrators thanks to the aforementioned pay-for-performance mandates issued by CMS which is clamping down Oct. 1 on hospital reimbursement for complications relating to infections. Infection control practitioners (ICPs), who have long been the front-line defenders against infections and adverse events, find themselves needing to bone up on risk management principles and fiscal concepts as they attempt to tally up the high costs of infections and make the business case for infection prevention.

In the midst of this turning tide are the other healthcare workers (HCWs) responsible for providing medical and surgical care to patients and who have been blamed as the guilty party for ignoring infection prevention principles and best practices — all in a daily rush to do their jobs amidst staffing and resource shortages triggered by razor-thin hospital budgets that keep getting thinner. Although healthcare workers know what to do, they don’t always do it.

Behavior modification and cultural change is the answer, as is a call for a transition from benchmarking to zero tolerance. But there are degrees of behavior modification initiatives, from the warm and fuzzy, to the punitive and everything in between. Denise M. Murphy, MPH, BSN, RN, CIC, president of the Association for Professionals in Infection Control and Epidemiology (APIC) and the chief patient safety and quality officer at Barnes-Jewish Hospital in St. Louis, alludes to a recent meeting of public health groups that discussed zero tolerance and concerns regarding the potential for a punitive response if hospitals set the goal at zero. “This could come from healthcare executives, or even the public, when an infection occurred despite compliance with known prevention measures and where no breakdown in safe practice was found,” Murphy says. “So we settled on language stating that we’re ‘targeting zero.’ One means of eliminating as many HAIs as possible will be zero tolerance for not adhering to infection prevention measures and broken systems that lead to harm.”2

Without a national standard or model, institutions are left to decide a course of action on their own. Either way, zero tolerance is taking on new urgency as healthcare institutions decide to take a stronger stance against the number of infections previously thought to be preventable. In a 2006 story on hospital infections, Washington Post reporter Christopher Lee quotes David B. Nash, chairman of the Department of Health Policy at Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia, as remarking, “The new wave of research is showing that our previous expectations around what was preventable underestimated what we could actually achieve. We can prevent more infections than we thought before. Lots of hospitals are striving to get to zero.”3

Noted infection prevention expert William Jarvis, MD, of Jarvis and Associates based in Hilton Head, S.C., alludes to the struggle over just how many infections are preventable. “There has been much debate over the years,” says Jarvis, who spent 23 years at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). “When I was at the CDC and I would say one-third of infections are preventable, a number of people would argue, ‘that’s way too high, you can’t do that.’ But with various collaboratives and other interventions in the last five to eight years, what we have seen is that a much higher proportion of infections is preventable, whether we are talking about surgical site infections, ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP), central line-associated bloodstream infections, or even methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infections. Interventions have prevented well over 50 percent and in some cases even 80 percent and 90 percent of infections, so now if we can get clinicians to implement the evidence-based recommendations that we know work, we will be very successful at preventing many infections.”

Jarvis continues, “Will we reach zero? No, but the attitude that I think we are moving toward, is one where clinicians don’t see these infections as inevitable. There are very sick patients who need a lot of invasive devices and procedures, so they are going to get infections. We need the attitude of trying to preventing all infections, and if one occurs, investigating to see what went wrong.”

Getting to zero is the basis of the “zero tolerance” of infections movement that has arisen in the last several years, promulgated by APIC. Murphy notes, “Why is the phrase ‘zero tolerance’ getting so much hype, and why should we be shaping what zero tolerance means in terms of infection prevention? Because too many people are still dying or being harmed by HAIs. We know the numbers because we compile them, but every number is someone’s loved one. Keeping people safe is the reason we do what we do — not rates. But rates and numbers measure our success so the goal must be elimination of HAIs, the metric or target must be zero. Zero is often possible. Many APIC members and their teams have set zero as the target and achieved that goal. They are truly saving lives.”2

Murphy says at that meeting among public health groups where zero tolerance was discussed, the concept was formally defined as “a culture, a goal, an attitude, and a commitment.” Murphy adds, “Infection prevention is no longer getting to a benchmark and stopping there. Zero tolerance means we must keep going, targeting zero. John Jernigan from CDC said, ‘In public health we talk about elimination all the time, about eliminating TB and other infectious diseases. So why wouldn’t we set a theoretical goal of zero even if we can’t prevent every infection because we cannot control all risk factors?’ Zero tolerance means treating every infection as if it should never happen, but when it does, we investigate the root cause. Finally, it means holding everyone accountable for HAIs, not just the ICPs.”2

Zero tolerance is creating a new infrastructure for infection prevention that includes other effective tools such as evidence-based interventions in the form of bundles. Jarvis writes, “… no single intervention prevents any HAI; rather a ‘bundle’ approach, using a package of multiple interventions based on evidence provided by the infection control community and implemented by a multidisciplinary team is the model for successful HAI prevention.” But an increasing number of researchers are acknowledging that addressing the behavioral aspects of infection prevention compliance is essential to fighting infections.1

Aboelela and colleagues4 note that attempts to address the growing problem of HAIs and their impact on healthcare systems have historically relied on infection control policies that recommend good hygiene through Standard Precautions. But they emphasize, “In order for infection control strategies to be effective, however, HCWs’ behavior must be congruent with these policies.” Aboelela and colleagues conducted a systematic review to evaluate studies testing the effectiveness of interventions aimed at changing HCWs’ behavior in reducing HAIs. Of 33 published studies, four studies reported significant reductions in HAI or colonization rates. Behavioral interventions used in these studies included an educational program, the formation of a multi-disciplinary quality improvement team, compliance monitoring and feedback, and a mandate to sign a hand hygiene requirement statement. In all 33 studies, bundles of two to five interventions were employed, making it difficult to determine the effectiveness of individual interventions. The researchers noted, “The usefulness of ‘care bundling’ has recently been recognized and recommended by the Institute for Healthcare Improvement. Considering the multifactorial nature of the HAI problem and the logistical and ethical difficulties of applying the randomized clinical trial approach to infection control research, it may be necessary to study interventions as sets of practices.”4

These practices — and their payoffs in fighting infections — have traditionally been evaluated through benchmarking activities. The one challenge with infection prevention is that much of it has been based on benchmarking among U.S. hospitals; Jarvis says that national benchmarking can be a less-than-ideal representation of infection rates across the country because it can be skewed toward large academic or teaching hospitals. “There has been this benchmarking mentality where people would look at their infection rate and then look at the CDC’s surveillance rates within the National Nosocomial Infections Surveillance System (NNIS), without realizing that they only really account for a small minority of hospitals in that system,” Jarvis explains. “Secondly, hospitals having less than 100 beds are not even allowed in that system, even though the average U.S. hospital is less than 100 beds. That means the majority of U.S. hospitals weren’t represented in that system — it was mostly academic centers that were providing the benchmarks. Everybody would look at that and say, ‘Well, if my infection rate is at or below the median of the NNIS system then I am fine, I don’t need to do anything.’”

Jarvis explains further, “The debate goes back to the mid-1970s, when the CDC conducted its landmark SENIC Project, the study of the efficacy of nosocomial infection control programs, which was a retrospective medical record chart review, and it was the first time that infection control was documented in a valid, scientific way to be cost effective and to prevent infections.” The SENIC Project was designed with three primary objectives: to determine whether (and, if so, to what degree) the implementation of infection surveillance and control programs (ISCPs) has lowered the rate of nosocomial infection, to describe the current status of ISCPs and infection rates, and to demonstrate the relationships among characteristics of hospitals and patients, components of ISCPs, and changes in the infection rate.

“At the time, no one really had a sense of what percent of infections were preventable,” Jarvis says. “Researchers conducted chart reviews and interviews about infection control programs and then they made estimates based upon the data they collected. They looked at which hospitals had epidemiologists and which had infection control professionals, how many did they have, what did they do, and then looked at programs in hospitals with lower infection rates compared to those who had higher infection rates and then made an estimate that in general, about one-third of HAIs were preventable. So it really was more of a guesstimate.”

In a 2007 white paper1 Jarvis underscored that benchmarking is inadequate and a culture of zero tolerance is required, as is a culture of accountability and administrative support. “In order to reach the goal of zero infections, hospitals need accountability,” Jarvis says. “In many U.S. hospitals, infection control programs are not well supported by administrators because they are not revenue-generating departments. Imagine a CEO at a hospital; two people from his facility offer him an option for the future; the first is the facility’s ICP. She says, ‘We can prevent many of these infections but we need more personnel. I’d like to hire one or two additional infection control personnel.’ She’s probably talking about less than $150,000 a year in salary costs, and you can prevent five infections. The next person who comes in is the chief of cardiovascular surgery who says, ‘I’d like to build a new operating room because I can do two or three coronary artery bypass procedures at $200,000 to $500,000 a pop.’ For the CEO, the decision is kind of a ‘duh!’ as to which decision he is going to make — she is always going to build the operating room.”

Jarvis continues, “Hospital CEOs and administrators must understand the importance of infection prevention and its impact on patient safety. They must realize it’s not about lip service, it’s about taking action and spending money to get to zero. There are a number of things happening that are getting the attention of hospital administrators, including CMS mandates, public reporting and other legislation at the state level. These things are bringing infections into the open, so hospital administrators are starting to see the light.”

If administrators are to see improvements in their facilities and not lose revenue from CMS, they are going to have to resolve the aforementioned issue of behavioral modification among clinicians. There are several classical battles being waged between ICPs and clinicians regarding compliance issues. One of the most enduring examples is that of hand hygiene compliance, which notoriously hovers around 30 percent to 40 percent. Studies indicate that HCWs wash their hands just one-third to one-half as often as they should.

Whitby and colleagues5 observe, “Although HCW compliance with handwashing guidelines is a cornerstone of ideal infection control practice, the rate of such compliance has proved to be abysmal.” For years, researchers have studied various interventions to discover how to improve HCWs’ knowledge of and compliance with handwashing guidelines and then reinforcing these practices. Whitby and colleagues note that “until recently, none have engendered evidence of sustained improvement during a protracted period.”

In 2000, two studies provided hope that handwashing practice could be improved. Pittet and colleagues.6 demonstrated that handwashing compliance among nurses at the University of Geneva hospitals increased to 66 percent during a 48-month period thanks to a number of interventions likely to affect HCW behavior including the provision of an alcohol-based hand rub designed to reduce the time taken and the inconvenience associated with handwashing. Larson and colleagues.7 described a significant increase in handwashing compliance that was sustained for 14 months in a Washington, D.C. teaching hospital. Their program attempted to induce organizational cultural change toward optimal hand hygiene, with senior administrative and clinical staff overtly promoting the handwashing program. Whitby and colleagues write, “Handwashing as a practice is a globally recognized phenomenon; however, the inability to motivate HCW compliance with handwashing guidelines suggests that handwashing behavior is complex. Human behavior is the result of multiple influences from our biological characteristics, environment, education, and culture.”5

For their study, Whitby and colleagues used the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB), explaining that with regard to handwashing, TPB is “predicated on a person’s acceptance that the immediate cause of handwashing is their antecedent intention to wash their hands. The intention to perform a given behavior is predicted directly, although to differing degrees, by three variables: attitude (a feeling that the behavior is associated with certain attributes or outcomes that may or may not be beneficial to the individual), subjective norms (a person’s perception of pressure from peers and other social groups), and perceived behavioral control (a person’s perception of the ease or difficulty in performing the behavior). These variables are predicted by the strength of the person’s beliefs about the outcomes of the behavior, normative beliefs (which are based on a person’s evaluation of the expectations of peers and other social groups), and control beliefs (which are based on a person’s perception of their ability to overcome obstacles or to enhance resources that facilitate or obstruct their undertaking of the behavior).

Whitby and colleagues’ investigations focused on elucidating and determining the origin of the behavioral determinants of handwashing in nurses in the healthcare setting. According to the researchers, handwashing was perceived by the study subjects foremost as a mechanism of self protection against harmful organisms. Handwashing behavior was also influenced by the appearance of their hands. Nurses recognized that handwashing played an integral role in the removal of microbes and the prevention of their transfer, and described the practice as unconscious and habitual, rather than as a thoughtful action associated with particular occasions.

Whitby and colleagues reported that although nurses appeared to believe that they habitually washed their hands without thinking about it, a number of factors appeared to affect the importance that they placed on handwashing in the healthcare setting, including the condition of their patients, the extent of patient contact, their assessment of the task involving a patient, and workload. They write, “Nurses believed that patients are a potential reservoir of infection because patients have little understanding of infection transmission. Nurses assessed the risk of infection due to contact with individual patients on the basis of several criteria, including the patient’s diagnosis, physical appearance, and perceived general cleanliness; visibility of the patient’s body fluids; and the patient’s age. An assessment was made in terms of the degree of ‘dirtiness’ or the lack of ‘cleanliness’ of a patient. Handwashing was not always considered to be essential for certain types of physical contact with patients. Tasks that require non-intimate touching of a patient or use of inanimate objects were less likely to be considered important motivating factors for handwashing, compared with tasks involving more-prolonged physical contact. In parallel with the nurse’s assessment of the task involving a patient, nurses judged the level of ‘dirtiness’ of the actual task. This assessment resulted in nursing staff feeling compelled to wash their hands if their hands were visibly contaminated, moist or gritty, or touched axillae, genitals or the groin. Nurses reported that, when under time constraints, they used physical and task assessments to determine the necessity of handwashing. However, nurses always felt compelled to wash hands after performing tasks they considered to be ‘dirty.’”5

Whitby and colleagues point out that attitudes toward physical contamination, such as fecal material, is consistent with a hypothesis developed by Curtis and Biran, who argue that the human emotion of “disgust” is an evolutionary protective response to environmental factors that may pose a risk of infection.8 Whitby and colleagues note, “This response may be mirrored in the way that nurses make judgments about the potential risk for infection that contact with a patient may pose. Their assessment of the need to wash hands was strongly influenced by the emotional concepts of ‘dirtiness’ and ‘cleanliness.’”5 Whitby and colleagues say their data suggest that an individual’s handwashing behavior is not a homogenous practice but falls into two broad categories. The first category, “inherent handwashing practice,” occurs when hands are visibly soiled or feel sticky or gritty and requires hand cleansing with water. The second category is “elective handwashing behavior,” which does not trigger an intrinsic response with an immediate desire to wash one’s hands; it represents to the nurse an elective opportunity for handwashing. Whitby and colleagues also indicate that because of perceived time constraints, nurses appear to act through a self-developed “hierarchy of risk” to determine when handwashing was necessary, thus ranking their opportunities for handwashing. When pressed for time, nurses assign lower priority to washing their hands than they do to other more urgent tasks.5

“A major component of zero tolerance is accountability,” Jarvis emphasizes. “In general, healthcare professionals are not taught about infection prevention in medical school or nursing school. We are not reaching them at a time when we could tell them this is critical to saving lives, so as a result many of them come out of training not thinking this is very important. Also, many clinicians think infection control is the infection control department’s job, not theirs. The fact is, infection control personnel should be the hospital’s consultants — they have the knowledge of what can and should be done to prevent infections, but they are not the people putting in IV lines or putting people on ventilators, they’re not the ones not doing hand hygiene, and that’s where accountability comes in. A number of large healthcare systems are taking a very aggressive approach against MRSA because the data show we can prevent many HAIs including MRSA. I was intrigued by a very large healthcare system whose CEO contacted the CEOs of each of the hospitals and told them in 2008 their yearend bonuses would be dependent upon how well they prevented MRSA infections. If you don’t think that’s going to make clinicians have some accountability, you’re nuts. The CEOs at each of those hospitals are going to ensure their clinicians are accountable for infections because it will impact the CEOs’ pockets.”

Jarvis continues, “Behavioral changes are key. One of the biggest challenges we have had in infection control is getting clinicians to do proper hand hygiene, and we have to admit that those of us in healthcare are absolutely atrocious at achieving behavioral change. If you look at changes in behavior, whether it’s wearing seatbelts or helmets or not smoking, we don’t change our behavior because of any kind of educational program, it’s because we have to obey the law — a law is passed and you have to wear a seatbelt or you get fined. We are very poor in our understanding of the capability to change HCW behavior. It’s why hospital CEOs and administrators must move that accountability down to unit directors. A good example of this is a surgical intensive care unit. We commonly see surgeons do a tremendous job of hand hygiene before they go into the OR; they gown and glove and mask and cap, and then they scream at anyone who violates infection control in the OR. Then they finish surgery, walk out of the OR, walk into the ICU and go from patient to patient to patient and don’t do hand hygiene. That kind of behavior must become a violation in the eyes of the unit director, who warns you one time and the second time you are out of there.

“It requires a tremendous change in our culture,” Jarvis says. “For example, there are no data to show that gowning and gloving and masking in the OR actually reduces infections — there has never been a randomized controlled trial. Yet if I went into any U.S. hospital wearing the clothes I have on right now and said I want to do surgery, there would be at least four people who would tackle me before I got to the OR — even though there are no data to suggest there would be a negative impact on patients if I did that. But it’s a cultural expectation in healthcare, and I think we have to change that culture throughout our hospitals with respect to infection prevention, where everyone is expected to do the right thing. And when they’re not, others tell them they must.”

APIC provided a startling insight late last year when it released findings from a non-scientific poll of ICPs asking them about changes made in their hospitals to better address MRSA infection rates.9 This poll came on the heels of APIC’s MRSA prevalence study, written by Jarvis. “APIC’s follow-survey showed that approximately 50 percent of the ICPs who responded to the poll said they had not done more to fight MRSA because they were not given the resources they needed by their hospital administration,” Jarvis says. “I think that will continue to be an issue and it’s only through public reporting and increasing state legislation that infection control program resourcing issues will be acknowledged. With CMS penalizing hospitals on one side and legislation on the other, the two of them are going to start squeezing, and hopefully this pressure will yield results in improved resourcing, reduced infections and the kind of healthcare all of us should expect.”

Murphy provides a 10-point plan10 for getting to zero:

1. Educate all healthcare providers about infection prevention

2. Educate hospital administration about infection prevention

3. Challenge HCWs to lead the charge against HAIs

4. Influence and educate stakeholders

5. Educate the community about infection prevention

6. Use and share meaningful infection data

7. Automate more tasks in infection prevention so more time is spent on education efforts

8. Learn how to make the business case for infection prevention

9. Develop strategic partnerships

10. Keep the patient at the center of all infection prevention efforts Murphy notes,

“What else do we need to do to get to zero? We need each other. ICPs worldwide need to persist, and together we can eliminate HAIs. We can broaden the range of what’s preventable. By partnering with patients and their families and healthcare teams, with researchers, educators, standards and law makers, industry, and innovators, we can work to establish a reliable system that prevents harm from infection. We must continue to negotiate effectively to get resources needed to prevent HAIs, and then we can ‘pay it forward’ to our patients and their families.2

APIC recently announced the launch of its “Targeting Zero” Initiative. For more details, go to: http://www.infectioncontroltoday.com/hotnews/targeting-zero-initiative-launched.html

References

1. Jarvis W. The United States approach to strategies in the battle against healthcare-associated infections, 2006: transitioning from benchmarking to zero tolerance and clinician accountability. Journal of Hospital Infection. Vol. 65. Pages 3-9.

2. Murphy DM. Go for zero then pay it forward. APIC News. Fall 2007.