Value of hospital accreditations under review

By YAMIL BERARD yberard@star-telegram.com

Christine Cahill, a government inspector, walked in to the operating room of a Los Angeles county hospital and found a technician cleaning a surgical instrument. He told her that he had just washed it, but she noticed no water in the sink, so she questioned how he had cleaned it, and he said he had used a cleaner that was in a bottle on the shelf.

"Give me a Q-Tip," she said. She shoved it into the hollow bore of the instrument.

"Out came this crud," she recalled. It was dried-up fragments of bone and blood.

At one out of every three hospitals Cahill surveyed for the federal government in California from 2004-06, she said she found egregious deficiencies that put patients’ lives at risk. Yet these same hospitals, within a year before her review, had received passing grades from the Joint Commission, America’s top healthcare evaluator.

It gave its most prestigious honor — its trademark Gold Seal of Approval — to Martin Luther King Jr./Drew Medical Center, where Cahill found the filthy surgical instrument.

And the commission also awarded that top honor, symbolizing that a hospital has met the most rigorous standards for patient care and safety, to John Peter Smith Hospital in Fort Worth in spring 2006 — the year before an independent consultant documented pervasive problems that put patients at risk.

Now, the Joint Commission itself is under review. For the first time in three decades, Congress is requiring the commission to reapply for authority to certify that hospitals meet federal standards. The commission has a virtual monopoly on hospital accreditation; 88 percent of the nation’s hospitals now choose it over a state agency.

The commission isn’t flinching over the new requirement. It posted a statement on its Web site saying it "is confident that it will receive deeming authority."

But Congress’ rare move opens up the application process to other organizations — including one in Houston that is drawing the interest of a number of Texas hospitals. Some member hospitals are griping that commission reviews often depart from Medicare standards, creating more compliance work.

For critics who characterize the relationship between the commission and client hospitals as too cozy, there couldn’t be a better time to shake up the status quo.

The situation resembles a "country-club-like setting," said Dr. Sidney Wolfe, director of Public Citizen’s Health Research Group in Washington, D.C., a consumers group. "What’s the point of having a regulator that’s a cheerleader over the institution they are supposed to be regulating?"

Scandals also fired up congressional debate last year involving the value of the commission’s accreditation. At issue were cases of accredited hospitals where patients got grossly inadequate treatment. One was a 14-bed West Texas facility where a patient died and federal officials reported that numerous staff members did not have adequate training for the medical procedures they were performing.

As a response to critics, the commission has been working in recent years to beef up its reviews. So-called unannounced visits — in which hospitals are given 48 hours’ warning — began a few years ago. Surveyors now track patients in the operating room and question doctors about diagnoses. What’s more, the agency responds not only to patient concerns, but to news reports of problems, as they did with JPS.

Commission surveyors arrived unannounced at JPS in June following Star-Telegram reports describing the JPS trauma center as a war zone, operating rooms as chaotic, instruments broken, rooms dirty, linens threadbare. Patients were put at risk when doctors couldn’t locate lab results or get crucial reports from specialists.

"We take all complaints seriously," commission spokeswoman Elizabeth Zhani said.

The inspectors cited a list of deficiencies, including intrusions into patient privacy, use of outdated drugs, filth and a system that could not keep track of narcotics, hospital officials said.

Such disturbing findings don’t mean the accreditation process is flawed, Zhani said.

"Accreditation is just not a [survey] visit," she said. "A lot of people tend to focus on that. We don’t know everything else that goes on."

"We cannot be there 365 days of the year," Zhani said.

But critics say the commission will be hard-pressed to identify a hazard so serious that it will shut down a hospital. It didn’t pull the accreditation from Martin Luther King Jr./Drew Medical Center until a year after Cahill conducted her survey — and the news media highlighted patient deaths tied to staff errors.

The Joint Commission process "in itself is, to say the least, superficial," Cahill said. "It doesn’t tell you what the hospital is doing."

Survey problems

The Joint Commission’s plan of attack has always been to "peer-review" or educate hospitals about quality standards, not regulate them, Zhani said.

"Organizations who contract with the Joint Commission are voluntarily saying: 'We want you to come in and survey us and inspect us to see if we’re following your standards for patient care,’ " Zhani said. "They are making a commitment that they want to focus on quality improvement."

But even supporters say the survey process has weaknesses.

Hospitals, no matter the size, are surveyed at least every three years. And the inspectors — usually independent contractors, not commission employees — spend about three days, often in back-to-back interviews with hospital administrators. Some say that doesn’t allow sufficient time for investigation.

At times, medical records are reviewed to make sure the proper documentation is there, not that patients received the proper medication, critics say. The focus of the surveys is on process rather than outcome, said Emily Moreno, a San Antonio registered nurse, now retired, who spent 30 years doing quality assurance at hospitals.

Even at that, though, a surveyor might have found what the JPS consultant did — that up to 20 percent of all medical records were missing.

It also isn’t clear to what degree hospital officials direct surveyors to departments or whether surveyors can — or have time to — wander around and just freely observe. That could explain why troubling problems were apparently overlooked at JPS.

Because the Joint Commission doesn’t make its reports available to the public, patients can’t be assured that surveyors visited some of the less conspicuous areas of the hospital, such as the unit that houses Tarrant County Jail inmates.

An independent consultant in 2007 noted a "dungeon like feel" to the unit and said that infectious patients were housed with noninfectious ones, with the potential of exposing patients, staff and sheriff’s deputies to such diseases as tuberculosis. Staff members told the consultant that the toilets were usually dirty and smelly, garbage cans regularly overflowed. Furniture was broken, and workspaces put doctors and nurses at risk of attack.

The Star-Telegram was not able to interview commission inspectors, despite repeated attempts.

When the survey turns up deficiencies, the commission works with hospitals to help them meet standards. And the commission continues to unveil better methods of identifying patient safety risks. One is a new practice in which surveyors "trace" or follow patients in surgery and other critical services in order to look for vulnerabilities in a hospital’s management of their care.

But critics say that the Joint Commission has other interests that may trump patient safety and lead the commission to stymie efforts that would strengthen compliance and public awareness of hospital problems.

For one, it relies on hospitals for the lion’s share of its $108 million in revenue. Hospitals pay tens of thousands of dollars for their survey evaluations. What’s more, the commission sells its consulting services to help hospitals meet accreditation standards. That boosts sales and creates the potential for conflicts of interest.

"It’s basically run by the [hospital] industry," said Julia Greene, a healthcare professional in Chicago with the Service Employees International Union, which has 2 million members, including the nation’s largest healthcare union.

Among those seeking change is the American Nurses Association, which blames the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services for failing to adequately supervise the commission’s role in the accreditation of hospitals.

Pressure is also coming from some groups concerned about rising healthcare costs. Business groups and insurers want to know if they are getting effective care for their money.

The Office of the Inspector General of DHHS is also expected to add fuel to the fire to revamp the commission. By winter, it is expected to release an examination of the commission’s accreditation process. The inspector general last reviewed the nonprofit in a scathing 1999 report that said its inspections were superficial and left little time for real scrutiny of a hospital’s errant practitioners — the ones most apt to do harm to patients.

Checks and balances

The government does provide some checks and balances to the commission in the form of federal validation surveys, such as Cahill’s at Martin Luther King Jr./Drew, which closed in August 2007 because of substandard conditions.

The surveys are conducted to validate the processes of the commission — "to make sure they’re doing what they’re supposed to be doing," Cahill said.

At most, only 5 percent of the nation’s hospitals undergo the federal scrutiny each year, she said.

But they always involve a team of specialists who spend a longer period studying a hospital, relying on a set of 19 health quality "conditions" required under Medicare regulations. For the MLK Jr./Drew Medical Center survey, Cahill was teamed with pharmacists, nutritionists, nurses and physicians. The surveys can last up to five days, and surveyors can visit the hospital four or five times to check to see that the hospital has corrected problems.

"When [government inspectors] do a validation survey based on the federal regulations, they are very, very thorough and the survey process is a much better process at finding problems than the Joint Commission would ever be," Cahill said.

While inspectors will suggest ways to improve, the survey is intended to root out bad practices, Cahill said.

If a medical record is reviewed, for example, government inspectors observe the patient’s care to see if the practice matches the hospital’s policy and federal standards, she said.

"We probe it further until we are convinced that it’s not an issue or it is an issue," she said.

That’s how inspectors found the case of a meningitis patient who had mistakenly received a potent anticancer drug for four days at the Los Angeles hospital.

Patients may also get some protection from state enforcement agencies. In June, Texas health inspectors were quick to arrive at JPS after news reports drew the commission back for a closer look. State inspectors are closer to the action and can add more layers of protection, the DHHS inspector general reported in 2000.

And next year, there may be a new face or two arriving to accredit hospitals in Texas. A Houston-based accreditation company — DNV Healthcare — is drawing the interest of a number of hospitals who say the commission’s standards deviate too far from Medicare rules.

The commission may have to reckon with the idea that, over time, it could lose its virtual monopoly on accreditation.

That’s all right with the Texas Hospital Association.

Competition "is a good thing . . .," says Starr West, senior director of policy analysis for the association.

"This sort of levels the playing field. We’ve been very supportive of having competition . . . it kind of keeps everybody in line."

Changes in hospitals sought Consumer advocates and other critics are pressing the Joint Commission to strengthen public accountability of hospitals. These are some of the changes being sought.

1 Disclose more information, including life-threatening medical errors and hospital deficiencies.

A commission manual states that hospitals are "encouraged" to report sentinel events, including patient suicide, abduction of newborns, foreign objects left in patients’ bodies during surgery and other major events. But hospitals are not required to do so. When a hospital does report, the commission usually does not identify it to the public. A national snapshot of reported sentinel events on the Joint Commission Web site shows just a map of the number of incidents by state.

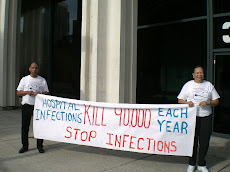

Releasing the names of hospitals where sentinel events occurred would be a small step in protecting the public, said Lisa McGiffert, senior policy analyst at Consumers Union in Austin, which publishes Consumer Reports. But even that wouldn’t provide the public with information it needs, she said. For example, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that almost 100,000 people die of hospital-acquired infections each year, yet in the past 13 years, the Joint Commission has classified only 105 cases as sentinel events, she said.

"If these sentinel events weren’t so misleading to the public, it’d be laughable," McGiffert said.

"The public has this belief that someone else is watching and making sure that hospitals are safe, and they are mistaken. Nobody is watching."

2 Make survey reports available to the public.

On its Web site, the commission publishes "Quality Reports" that compare a hospital’s performance in a handful of areas to that of other hospitals. For example, John Peter Smith Hospital’s report shows that in 2007 it rated below most accredited hospitals in the country when it comes to heart attack care. ( www.qualitycheck.org/qualityreport.aspx?hcoid=9048#)

But it’s left up to hospitals to decide whether to disclose deficiencies noted by surveyors. After commission inspectors paid a surprise visit to JPS this summer, the hospital made public some findings but did not release the report and specific deficiencies.

"If the organization wants to release the report, they can release it," Joint Commission spokeswoman Elizabeth Zhani said.

3 Pay more heed to patient complaints.

Emily Moreno of San Antonio, who focused on hospital quality during her 30 years as a registered nurse, filed a complaint with the commission after she developed an infection at the site of a breast biopsy at an Oklahoma City hospital. The commission had accredited the hospital seven months earlier.

It took no action on her complaint, she said. It only told her, in response, that it gives "serious consideration" to all complaints.

Susan Sheridan, an Idaho mother of a child with cerebral palsy, did get the commission’s attention. Her son, now 13, suffered brain damage because of the failure of hospitals to test newborns for jaundice. She and other mothers of children with cerebral palsy co-founded Parents of Infants of Children with Kernicterus. Thanks to her advocacy, hospitals now test for excessive bilirubin levels in newborns.

4 Place more patient representatives on the commission board.

Sheridan would also like to see the commission open up more hospital data to the public, but doesn’t believe that will happen soon.

"Their very structure stifles that," she said. Most of its board members are doctors or health practitioners.

"What ties their hands basically is that its members and their clients are hospitals," she said.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment