By Michael J. Berens and Ken Armstrong

Seattle Times staff reporters

A night-shift nurse slipped into Jeanine Thomas' hospital room and whispered, "I don't know how you're taking this so well. If I were you, I'd be curled up in a ball crying."

The remark mystified Thomas. She'd had ankle surgery, and yes, there had been complications. But she thought she was recovering. Was there something she didn't know?

In November 2000, Thomas, then a 45-year-old antiques dealer, had slipped on ice and shattered her left ankle outside her suburban Chicago home. But days after surgery at her local hospital, the skin surrounding the incisions turned black, and her body swelled. Doctors wanted to amputate, but Thomas, an avid tennis player, refused to let them.

Then, a friend told Thomas about her mother's battle with MRSA, an antibiotic-resistan t germ. Their symptoms matched. Thomas confronted a doctor and learned the truth: She, too, had MRSA. Only now did the nurse's comment make sense.

Thomas asked doctors how many people get MRSA. She was met by silence.

"That's when I knew — a light bulb went on in my head," she says. "They don't want anyone to know about this."

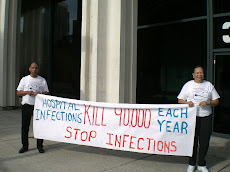

Today, Thomas is exposing MRSA's staggering toll as one of the nation's most influential patient advocates. Because of her persistence, Illinois hospitals now must disclose MRSA infection rates and screen for the germ. She's also pushing for federal legislation that could enhance patient safety in Washington and every other state.

Thomas epitomizes a revolt in health care. A growing number of consumer advocates — many bound by ordeals with MRSA, or methicillin- resistant Staphylococcus aureus — have vowed that if the U.S. Hospital system will not heal itself, they will do it.

Five years ago, not a single state forced hospitals to reveal how many patients contracted infections while under their care. Now 25 states have some form of "report card" disclosure that can make hospitals more accountable.

Washington has a report card; it tracks three kinds of infections — but not MRSA.

MRSA rates in Washington have increased 33-fold in the past decade, a Seattle Times analysis shows. Last year, 4,723 hospital patients were diagnosed with the infection.

With fanfare, the state launched two initiatives last year to combat the epidemic. But in the end, neither made much difference.

In Washington, no patient advocate like Thomas has emerged.

Advocates gain ground

Across the country, consumer advocates have embraced two tools — MRSA screening and hospital report cards — to make hospitals more transparent and aggressive when dealing with infections.

The more popular has been report cards, often a byproduct of patient frustration with hospital secrecy and inadequate infection control.

Chris Cahill, a consumer advocate, worked with legislators to pass a report-card law this year in California.

Before retiring in 2006, Cahill worked for 12 years as a hospital surveyor for the California Department of Health Services. She inspected dozens of hospitals and saw how they could become easy targets for contagion. Some hospitals are "so filthy and dirty it's just incredible," she says.

Many infection-control departments, a cornerstone of patient safety, have so little staff and equipment that it's impossible to track every germ or consistently enforce standards, she says. Even large hospitals often put infection control in the hands of just one or two nurses.

"Many hospitals see infection control as a necessary evil. All they see is the bottom line," Cahill says.

That so many states have recently adopted hospital report cards shows how influential consumer advocates have become. But the hospital industry has often pushed back.

Some hospital officials believe consumers will draw unfair comparisons from report cards, without considering how each hospital has different patient populations. A hospital with a trauma center will have more patients who are vulnerable than one that focuses on elective surgeries.

Lawmakers in some states have passed report cards that provide little information to the public.

In Nevada and Nebraska, hospitals now must report infections to state health officials. But to the public, the numbers remain locked away.

Arkansas encourages hospitals to report infection rates — if they want to. Most don't.

"Not essential right now"

Washington passed its own report-card act in spring 2007. But hospitals have to report only one kind of infection this year: bloodstream maladies in patients who receive a central-line intravenous hookup. The report card will add a second type of infection next year, and a third by 2010. But MRSA is not among them.

Twice before, report-card legislation had died in Washington, after drawing fierce opposition from the hospital industry. The current measure represents a compromise or a first step, said state Rep. Tom Campbell, R-Roy, who sponsored the bill.

In Washington, MRSA has been linked to 1,217 deaths in the past decade, a Seattle Times analysis of hospital records shows. At least 23,707 hospital patients have been diagnosed with MRSA infections.

One Seattle hospital estimates that it costs $20,000 to treat a MRSA infection. Using that figure, MRSA's financial toll in Washington exceeds $474 million.

In the report-card bill, Washington lawmakers had included $240,000 for state health officials to investigate MRSA outbreaks, establish surveillance programs and educate health-care workers and the public about stopping the germ's spread.

The Washington Hospital Association supported the measure, which would have allotted public money to address MRSA.

But Gov. Christine Gregoire stripped the provision out, along with all kinds of other spending items. Her veto notes called the measure "valuable" but "not essential to do right now."

The Illinois fight begins

While hospital report cards have been enacted in much of the country, legislation requiring hospitals to screen patients for MRSA has been difficult to pass.

When Jeanine Thomas contracted MRSA in 2000, no state had even considered such a law. Her success in changing the culture has become a strategic blueprint for consumers in other states, where hospital resistance to mandated screening remains steadfast.

After her ankle healed enough that she could walk, Thomas cobbled together bits and pieces of information about a germ that few seemed to know about.

In 2003, she helped muster support for a bill requiring Illinois hospitals to disclose infection rates. A state senator named Barack Obama co-sponsored the legislation, which passed that year.

The experience inspired Thomas. She began campaigning for a law that would require hospitals to screen patients for MRSA. The screening test, which costs about $20, allows hospitals to identify who has the germ and to isolate them, to protect other patients.

Thomas wrote letters to state legislators and spoke out at health-care meetings. She said doctors undecided about screening had adopted a "compromise of doing nothing."

To combat the medical establishment, she received help from two of the nation's leading infection-control experts. One was Dr. Barry Farr, who was retired from the University of Virginia. Farr had urged hospitals since the 1980s to adopt aggressive screening programs, but he often met with resistance.

The other was Dr. William Jarvis, former acting director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Jarvis also supported screening, and sparred with its opponents at infection-control conferences.

"The public is tired of waiting for us to decide this debate and move into action," he says.

By late 2005, Thomas had forged an alliance with Illinois state Sen. Christine Radogno, who agreed to sponsor legislation that would mandate MRSA screening. If passed, the law would be the nation's first.

Thomas later wrote a note about her meeting with Radogno: "She told me tell no one."

They agreed that stealth was necessary because a war was about to begin.

Maryland bill fails

In Maryland, a home contractor from Baltimore had already started a similar war.

Michael Bennett created the Coalition for Patients' Rights after his 88-year-old father, Mark, contracted MRSA at a local hospital. A week after getting MRSA, his father picked up two more antibiotic-resistan t germs. Those infections touched off necrotizing fasciitis — also called flesh-eating disease — and his leg was amputated.

Bennett's father was transferred to a series of rehabilitation centers. There he picked up three more infections, which destroyed his kidneys and poisoned his blood before killing him in June 2004.

While his father was in the hospital, Bennett says, doctors let two months pass before revealing the MRSA diagnosis. During that time, he says, dozens of staffers could have spread the germ. They only occasionally wore gloves or gowns or washed their hands after caring for his father.

In 2005, Bennett helped get legislation introduced to mandate MRSA screening in Maryland.

"Hospital infections have been killing too many for far too long," he says.

But the bill received what Bennett calls a "barrage of criticism" from hospital-industry officials, and it went down to defeat. Bennett tried again in 2006 and 2007, but with the same result.

The first breakthrough

When the Illinois MRSA legislation was introduced in January 2006, a firestorm erupted.

National medical groups attacked the bill, challenging screening's benefits and costs while touting existing infection-control measures, such as hand hygiene. The bill died in a House committee.

But Thomas tried again.

The first public hearing was held in February 2007 in downtown Chicago, during a fierce snowstorm. Many opponents showed up; Thomas was the lone supporter.

The Illinois Hospital Association originally opposed Thomas, fearing her proposal would force hospitals to test every patient. Later, when assured the scope was limited to critically ill patients and others at high risk of contracting MRSA, the association supported the measure.

The association had conducted research of patient-discharge data — the same kind of analysis The Seattle Times did in Washington — and was stunned at how many MRSA cases it found, Thomas says.

In May 2007, the bill passed the Illinois Legislature. The House vote was 106-0.

Thomas immediately called Farr: "He was overcome. He said he had waited so long for this."

But in August, an aide to Gov. Rod Blagojevich called and told Thomas the governor intended to veto the bill. His office issued a news release saying as much. Thomas, crying, began working the phones, rallying legislators to flood the governor with calls.

A few hours later, the governor changed his mind and signed the bill.

Three other states — Pennsylvania, New Jersey and California — have since passed similar screening laws.

"Impractical or extreme"

Washington, like the rest of the country, was rattled last October by the highly publicized announcement of the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention that MRSA now kills more people than AIDS.

Some schools closed temporarily over a single MRSA infection, or canceled football games so locker rooms could be disinfected.

In November, Gregoire wrote to the state Health Department, saying: "We need to do more." She ordered the agency to collect MRSA test results from medical laboratories statewide, and to create a panel of experts to recommend ways to curb MRSA's spread.

"Gregoire takes on superbug," a Seattle Times headline said.

But a year later, these two unfunded initiatives have had little effect.

The reporting of test results was voluntary, so some labs did not submit them. In other cases, the information was so sketchy that state officials couldn't tell where people caught the germ.

"We didn't find a whole lot of meaningful data," says Judith May, the Health Department's acting director of epidemiology.

As for the expert panel, it was stacked with hospital representatives, without a single consumer advocate. In January, the 18-member panel published its MRSA report — an 82-page rehash of existing medical literature.

The panel opposed screening all patients for MRSA, calling it "impractical or extreme ... with little added value."

Instead, it recommended that hospitals use infection-control guidelines from the CDC. But those guidelines have been widely criticized by congressional investigators, who call them confusing and conflicting.

In Washington, most community hospitals make these guidelines the core of their infection-control programs. None tests every patient for MRSA.

Last month, a representative of the Illinois Hospital Association met with a few dozen Washington hospital officials and touted the benefits of widespread MRSA screening.

For the first time, Illinois is getting a true picture of MRSA's toll, the representative told them.

Last year, the Illinois hospital group found approximately 11,300 MRSA cases. But this year, with screening in full force, the group estimates the number could be close to 30,000.

The fight continues

Today, Jeanine Thomas runs the MRSA Survivors Network.

She's haunted by memories of her time in the hospital, when she rolled up and down the corridors in a wheelchair, or grabbed coffee in the cafeteria, or used the drinking fountains.

"For two months I didn't know I had this infectious germ. The hospital let me go wherever I wanted.

"How many people did I infect?"

These days, she is campaigning for a federal law to mandate hospital MRSA screening in every state.

She criticizes Washington's refusal to embrace widespread screening, saying many of its hospitals are endangering patients.

Her Web page links to survivor stories, from a mother who lost her 7-week-old daughter to MRSA to a 58-year-old man who lost much of his left leg.

Thomas points to these survivors when confronting critics of MRSA screening.

"I'm trying to save lives," she tells them. "What are you trying to save?"

Michael J. Berens: mberens@seattletime s.com or 206-464-2288; Ken Armstrong: karmstrong@seattlet imes.com or 206-464-3730. Reporter Justin Mayo and researchers David Turim and Gene Balk contributed.

Copyright © 2008 The Seattle Times Company

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment