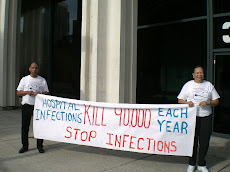

Hospital infection deaths caused by ignorance and neglect, survey finds

By N.C. Aizenman

Washington Post Staff Writer

Tuesday, July 13, 2010; A03

Deadly yet easily preventable bloodstream infections continue to plague American hospitals because facility administrators fail to commit resources and attention to the problem, according to a survey of medical professionals released Monday.

An estimated 80,000 patients per year develop catheter-related bloodstream infections, or CRBSIs -- which can occur when tubes that are inserted into a vein to monitor blood flow or deliver medication and nutrients are improperly prepared or left in longer than necessary. About 30,000 patients die as a result, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, accounting for nearly a third of annual deaths from hospital-acquired infections in the United States.

Yet evidence suggests hospital workers could all but eliminate CRBSIs by following a five-step checklist that is stunningly basic: (1) Wash hands with soap; (2) clean patient's skin with an effective antiseptic; (3) put sterile drapes over the entire patient; (4) wear a sterile mask, hat, gown and gloves; (5) put a sterile dressing over the catheter site.

The approach also calls for clinicians to continually reconsider whether the benefits of keeping the catheter in for another day outweigh the risks and to use electronic monitoring systems that allow them to spot infections quickly and assemble a rapid response team to treat them.

A federally funded program implementing these measures in intensive-care units in Michigan hospitals reduced the incidence of CRBSIs by two-thirds, saving more than 1,500 lives and $200 million in the first 18 months. Similar initiatives across the country helped bring the overall national rate of these and related bloodstream infections down by 18 percent in the first six months of 2010, according to the CDC.

"Our research shows that the cost of implementing [such programs] is about $3,000 per infection, while an infection costs between $30,000 to $36,000," said Peter Pronovost, a professor at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine who led the program. "That means an average hospital saves $1 million."

So why aren't hospitals leaping to adopt these best practices?

The survey released Monday, which was conducted by the Association for Professionals in Infection Control and Epidemiology and funded by Bard Access Systems, a maker of catheters, pointed to ignorance and neglect at the top.

More than half of the 2,075 respondents, most of whom were infection control nurses employed by hospitals, reported that they use a cumbersome paper-based system for tracking patients' conditions that makes it harder to spot infections in real time. Seven in 10 said they are not given enough time to train other hospital workers on proper procedures. Nearly a third said enforcing best practice guidelines was their greatest challenge, and one in five said administrators were not willing to spend the necessary money to prevent CRBSIs.

Pronovost said part of the problem was that many hospital chief executives aren't even aware of their institution's bloodstream infection rates, let alone how easily they could bring them down.

When hospital leaders decide to create a culture in which preventing infections is a priority, he added, nurses feel empowered to remind physicians to follow the checklist when inserting catheters, physicians are provided antiseptic soaps as part of their catheter kits and infection control personnel have the best tools to monitor patients.

"If anyone in that chain of accountability doesn't work, you won't get your [infection] rates down," he said. "But it's the hospital's senior leadership that is ultimately responsible."

1 comment:

This really seems to be very serious. I am hoping that those who are responsible for this cases would prioritize on preventing this infections that already took almost half of its cases.

Ashley

disinfecting cap

Post a Comment