Reform should make it easy to get information on quality

Reform should make it easy to get information on qualityAugust 2009

'I lay in my hospital bed watching my stomach turn black and purple and rot. It looked as if I had been snapped in half by a shark.'— Alicia Cole, 46, of Sherman Oaks, Calif.Photo by Melanie Eve Barocas

This article is the archived version of a report that appeared in the August 2009 Consumer Reports magazine.

When Alicia Cole learned she needed surgery for benign fibroids, she did her homework on the surgeon and the hospital. "I looked at HealthGrades, Leapfrog, Hospital Compare, and other Web sites," says Cole, a 46-year-old actress from Sherman Oaks, Calif. "But one thing I didn't check was the hospital's infection rate."

Even if she had tried to check, California hospitals didn't have to make such data public, and hers didn't. Cole had the operation there anyway. During her hospital stay, she came down with a post-surgical flesh-eating infection that turned her entire midsection into something worthy of a horror movie. After two months in the hospital and two years of painful rehabilitation, she still can't work. "The skin and scar tissue is so delicate that the least pressure will tear or scratch it," she says. Federal inspectors subsequently found unsterile conditions in the hospital's operating area.

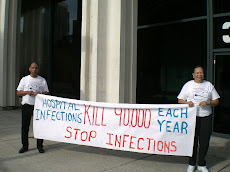

Enraged by her experience, Cole joined the fight against hospital infections and helped persuade the California legislature to pass a law requiring public reporting; she now sits on the advisory board for the law. Did she ever learn the hospital's infection rate? Sadly, no. The law has not yet been implemented. "What we really need is a national law," Cole says, noting that hospital-acquired infections are a leading cause of death in this country. "It's the elephant in the room," she says.

CU recommends

Health reform should make it simple to get good information on health-care quality. You should be able to find data not only on infection rates, a reform we've backed for years, but also on doctors, drugs, treatments, and errors. Yet most states still allow doctors to shield a history of malpractice settlements. And infection rates, if reported at all, are often kept secret, which doesn't provide enough incentive for improvement.

What does work is disclosure. Pennsylvania, which passed the first statewide reporting law, remains the only state to require disclosure of all major types of hospital infections. And infections there have dropped 8 percent in the last two years.

Read about our latest reform efforts and our analysis of legislation as its being debated in Washington, D.C. in our Guide to Health-Care Reform.

No comments:

Post a Comment